Isla Encantada: Six Days on a Desert Island

(Photo: Gregory Adams / Moment via Getty Images)

There is a small desert island off the west coast of Mexico called Isla Encantada. Though it is nearly 20 miles long and 5 to 10 miles wide, nobody lives there. Nobody human, that is. So far as one can judge from the scanty archaeological evidence, humans have never lived on the island. There is a good reason for this omission, so unusual in our otherwise overcrowded world: Encantada is waterless. There is no stream, no spring, no permanent surface water whatsoever. And because the island is composed entirely of highly porous, nonaquiferous volcanic rock, it is probable that little, if any, water could be obtained by drilling a well. In any case, the Mexicans have not attempted it; there are no wells. Isla Encantada is a true desert isle, waterless, uninhabited, worthless, and—in its unhuman fashion—quite beautiful and perfect.

My friend Clair Quist and I flew there one winter day, about a year ago, in a plane piloted by Ike Russell, a veteran desert bush pilot from Tucson. Ike put us down on a dry lake bed—there are no legitimate landing strips on the island—and took off, having promised to return for us in a week. Clair and I set up our camp on a high point with a good view of a curving pebbled beach, within earshot of the surf. Camp consisted of his bedroll over there and my bedroll over here, about a quarter-mile apart. (Clair and I are not nice or sociable people.) In between, beside the shade of a knee-high bursera shrub, was our base headquarters. Headquarters was created by juxtaposing four flat rocks: two supporting the grill on which we did our cooking, and two for sitting on. Clair’s rock was more comfortable than mine, but I could sit on his only when he was not around. We provided no guest rocks.

We hid our food and our 15 gallons of water under the bursera and spent most of the next six days exploring our end, the southern end, of the island. We did a lot of walking but made no overnight hikes, for several good reasons: It was too hot; it was too humid; the island is mountainous; there is no water; we were unwilling to carry water; and—we didn’t feel like it. Clair and I are working men, unlike most people we know, and earn a large part of our income by doing things similar to backpacking. (He is a professional river guide; I look out for forest fires.) We were on vacation, free at last from the daily grind, and weren’t about to spoil it all by strapping a load of pig iron to our backs.

We explored the mountains; we explored the sea. Staggering over the slime-covered shingle of the beach, we waded into rollicking waves, put on goggles, and cruised the underwater realm. Schools of golden sunfish, flowering with the grace and unison of ballet dancers, passed beneath us. Small, timid, and frightened stingrays, half buried and wholly camouflaged in the white sand, scurried away at our approach. Once I saw some kind of small shark, no more than 3 feet long, dark as a shadow, glide away into the deeper gloom offshore.

We prowled the beaches, littered with wrack from the sea: mescal bottles turning blue in the sun; tangled fishing lines and torn nets; the bones and skulls of pelicans, blowfish, turtles, sea gulls, sharks, giant lizards; the rotting corpse of a young sea lion; Clorox bottles; seashells and sand dollars, and other forms of ceramic ocean currency; salt-encrusted, surf-eroded wooden boxes, boards and broken water casks; wordless messages from all parts of the wide, wild, extravagant Pacific.

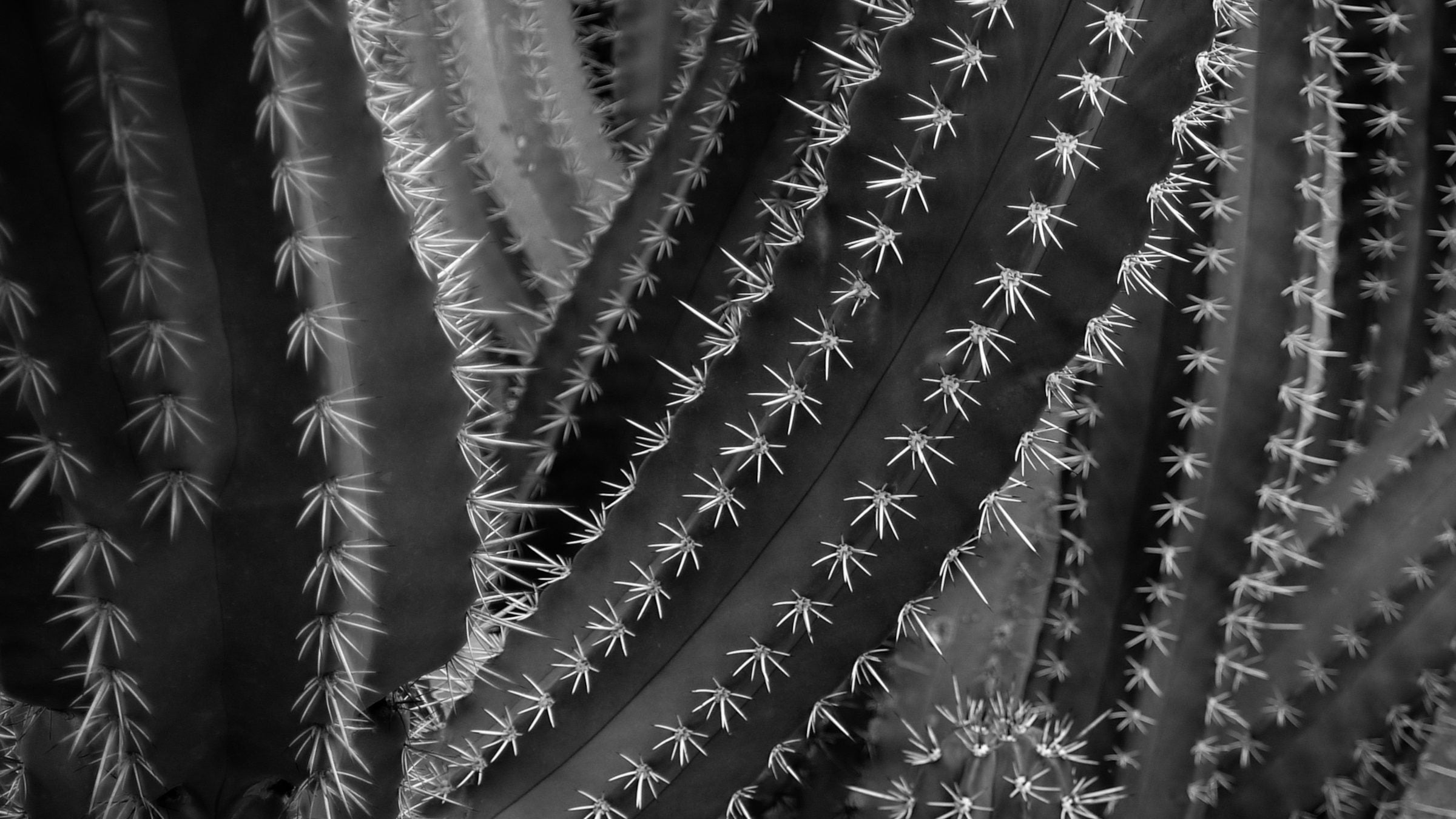

We wandered through the strange, tropical desert. I said there was no water on this island, no surface water at least, and that is mostly true. (The exception will be described later.) But there is rain now and then, enough to support a variety of Sonoran Desert-type plant life. We found groves of the great cardon cactus—a thorny, massive, sun-bronzed succulent with the look of hammered metal. The biggest cardons were about 40 feet tall, much thicker and heavier than the familiar saguaros of southern Arizona.

Scattered about in all the rocky drainages were ironwood trees, both living and dead. The wood of this tree lives up to its name. Its heart is heavy enough to sink in water and hard enough to chip an axe blade. The dead ironwoods have a coppery hue and resemble abstract sculpture; because the wood is so durable, even the smaller branches and twigs survive in place and form long after the death of the tree. Hard, but brittle, it is easy to break, and it makes an excellent cooking fuel, burning hot and clear. We used some of it for our fires, but not without guilt. This rare and splendid tree is being gradually eliminated throughout much of its mainland range by the fuel needs of the rapidly multiplying Mexican population.

We climbed the rotten, barren volcanic hills. The highest point in the south of the island is some 3,000 feet above the sea. Guided by doves, we found, in a small canyon carved by erosion in the bedrock, some natural stone tanks, or tinajas, as the Mexicans call them, partly filled with water from the last of the winter rains. Good water; we drank and filled our canteens; but the little potholes were many miles from camp and not a reliable source. Within a week or two they would be dry as the desert below. No wonder nobody lives here.

Nobody but the lizards, the arachnids, a few reptiles and the birds. We saw no sign at all of any form of mammalian life—no fox, no coyote, no hare or rabbit—except the tiny desert rodents, such as kangaroo mice, that are capable of manufacturing their own internal “metabolic” water from the air they breathe and the dried seeds that form the staple of their diet. Of the lizards the most common is the chuckwalla, a fat, leathery, and sluggish creature so lazy or so unafraid that we could have caught them by the bushel if we wanted to. They can be eaten; the hawks and sea gulls eat them; the desert Indians of the Southwest used to eat them (before they discovered welfare and Wonder Bread and Pepsi-Cola); but they look about as appetizing, these miniature dragons, as my old beatnik Jesus shoes.

We saw one diamondback rattlesnake coiled among the flowers that were blooming, however briefly, in the cactus garden of a place we named Paradise Valley. So far as we knew, or our rudimentary map indicated, nothing had been named on Isla Encantada but the island itself. Like reincarnated Adams, we felt obliged to bestow on the vales and peaks and swales and bays of this neglected island those labels which it lacked, those tags of identity so dear to the restless, rootless, human psyche. What’s in a name? Our sense—or the illusion—of understanding. If we name it we think we know it. Our names were a little obvious. A canyon with fan palms we named Palm Canyon. The canyon with the waterhole we named Waterhole Canyon. Our beach we named Pebble Beach. Why be clever?

On the fifth—or was it the sixth?— day of our stay on this enchanted island, this sea-girded world left over from the Dream time, as the aborigines would say, the spell was somewhat broken, or at least bent, by the arrival of Ike Russell and his airplane. Out of the airplane stepped Douglas Peacock and Terry More, old friends of mine. Of course we knew they were coming; we’d invited them to join us. Ike took off and returned in an hour with two more folks—friends of Moore. Good men, all of them, that the island was getting just a little bit overstuffed. The population was exploding like bacteria in a culture bouillon. We left the next day.

And learned, too late, that we’d mist the best part of the island. Flying toward the mainland, we passed the north end of the island and saw beaches, craggy headlands, rugged offshore island crowded with herds of sea lions—all fringed in white foam, encircled by the wine-dark sea. Even the peaks looked higher, more violent in form and color, like the Funeral Range—Death Valley-by-the-Sea. Dammit, Clair, let’s jump this here flying machine (I was thinking). And he was thinking the same thought, I learned an hour later back in the dusty wastes of Caborca, Mexico.

Terry and his friends did not miss it. They spent most of their week on those sandy beaches, among the happy isles. And Doug Peacock did best of all, staying on alone for another week. There he feasted on clams dug up from the beach and once, as an experiment, caught, roasted, and ate a chuckwalla. Not bad, he claims, not half bad. In all those days of magic solitude he saw only one boat pass by the island, a small sailing ship which put in, for one night, on his beach. His beach. Yes, regrettably, one does get possessive about these places.

That island is still out there, down there, alone in the glittering Pacific, haunted by sea lions, mermaids, the hawk, the dove, and the noble pelican. We’ll return, someday, and maybe find the secret—if it is a secret—of Isla Encantada’s mesmerizing silence.