Confessions of a Reluctant Highpointer

'John S. Dykes'

“Pull over,” I said.

We were headed down a two-lane highway south of Timm’s Hill County Park, through the thick green woods of north-central Wisconsin. This was supposed to be a laid-back week, hitting four easy state highpoints: Eagle Mountain (Minnesota, 2,301 feet), Mt. Arvon (Michigan, 1,979 feet), Timms Hill (Wisconsin, 1,951 feet), and Hawkeye Point (Iowa, 1,670 feet). In between, we’d use the extra days to hike the Boundary Waters’ forests, explore the cliffs and beaches of the Apostle Islands, and wander the dunes and pancaked sandstone cliffs of Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore. It was just after Labor Day weekend—no crowds, clear skies, summer heat subsiding. It was a good plan: We’d pace ourselves and see the area’s most renowned wild places.

Instead, after tagging Timms Hill—with nearly a thousand miles of driving and two other highpoints behind us and three days to go—I had a new idea. It did not include the Boundary Waters.

Audra steered our rented Chevy subcompact into the gravel lot next to an old train depot, tires crunching to a stop. I called up Google Maps on my phone and reached into the door pocket for our well-worn copy of Don Holmes’s Highpoints of the United States, its laminated cover peeling. I thumbed to the U.S. map in the front of the book, then typed “White Butte, ND” on my phone.

“Oh, no. That’s insane,” Audra said in an accusatory tone that couldn’t quite hide a tinge of excitement.

I continued to punch in the new route and made my case. “If we drive to Minneapolis now, then leave by six tomorrow morning,” I said, “we can be at the White Butte summit by early afternoon.” Then, we’d finish a marathon push to Rapid City, South Dakota. The following day we’d snag Black Elk Peak (South Dakota, 7,242 feet), then hit Hawkeye Point on the way back to the Minneapolis airport. “We should have an hour or so to spare before our flight,” I said. “Hopefully.”

Yes, it would mean we’d pack our “laid-back” vacation with an extra 20 hours and 1,200 miles of driving. It would mean forgoing the Boundary Waters. It would mean trading the Apostle Islands for a 1-mile hike to a nondescript butte on private land.

But it would also mean checking off two more state highpoints.

Had it really come to this? Audra put the Chevy in gear.

Highpointing. Talk to most people who call themselves highpointers, and they’ll tell you about the moment they committed to the goal, perhaps the peak that got them hooked.

Not me. I don’t have a single moment. If anything, I thought the idea was pretty dumb when I first encountered it. Nineteen years ago, I stumbled upon a copy of Highpoints of the United States on the “free table” at the short-lived outdoor magazine where I worked.

I flipped through the pages and learned I had summited exactly one—Washington’s 14,410-foot Mt. Rainier—the year before on a guided trip. I also learned that the highpoint of Alabama, where I grew up, is 2,407-foot Cheaha Mountain, and that you can drive right up to the restaurant and observation tower at the summit.

Fairly quickly, I realized that half of the state highpoints are, like Alabama’s, not climbs at all, or even hikes: They are bumps and hills that can be accessed by roads all the way to the summit parking lot. Delaware’s highpoint, I read, was 448-foot Ebright Azimuth, an indistinguishable swell on a suburban street corner north of Wilmington. I guess that’s why they’re called highpoints and not summits. Some highpoints like Connecticut’s Mount Frissell are actually on the side of a peak whose summit is in another state, in this case, Massachusetts.

Of course, some are summits, and require great effort or technical skill or both. As a weekend adventurer and budding mountaineer, I had already penciled some of these classics on my bucket list, like Mt. Hood (Oregon, 11,240 feet). But Cheaha Mountain? Ebright Azimuth? Pursuing them seemed the very definition of inane. The locations on this list are determined by arbitrary state lines. In the rules of this game, standing on the corner of someone’s manicured yard shares equal status with standing on the summit of Denali (Alaska, 20,310 feet).

Still, it was fun trivia, so I brought the book home. And I suppose it’s telling that in the personal log appendix, in writing so measured that today I don’t quite recognize it as my own, I wrote “6/17/99” next to Washington, Mt. Rainier, before putting the book on my shelf, where it sat untouched for years.

The book drew Audra’s attention like a magnet. We’d only been dating a short time when she picked it up. As a natural obsessive who isn’t happy unless she has a goal—a marathon, an Ironman, basically anything that requires planning and diligent checking-off of milestones—she was fascinated by the list.

By then I had hiked a few more peaks that incidentally were also highpoints: Mt. Marcy (New York, 5,344 feet) and Mt. Mansfield (Vermont, 4,393 feet). They were easy weekend trips from my home in New York City—and were actual hikes. Audra saw the dates written in the personal log and kept asking when I was doing more. “No idea,” I’d respond each time, “I’m not trying to do them.”

Audra ignored me and started consulting the book whenever we traveled. It was her idea to detour to the Delaware highpoint on a winter weekend when we were visiting friends in Philadelphia. I resisted. “It’s not even a hike,” I said.

“It’s only 25 miles out of our way,” she argued. And won.

“Turn right at the light,” Audra said, using the book to read me directions to Ebright Azimuth. At the light, I turned off the four-lane highway onto a neighborhood road. A few blocks later, we pulled up next to a blue-and-gold historic sign on the edge of someone’s yard (the property was formerly owned by the Ebrights). It’s only about 420 horizontal feet from the Pennsylvania border, but at 447.85 feet high, it’s deemed to be the highest natural earth in the state.

I walked through 2 inches of sooty snow toward the sign in mock slow motion, taking gasping breaths like a mountaineer at elevation, and tagged it with a playful slap. We took each other’s pictures next to the sign, wearing smart-ass grins and faces of sarcastic pride. It was her first highpoint, my eighth: “2/21/05.”

Over the next few years, Audra found ways to sneak two more highpoints into our plans while we were doing other things. Going to Cape Cod for a group beach house rental one summer, it was less than an hour’s detour to Jerimoth Hill (Rhode Island, 812 feet), another spot next to someone’s yard. Hiking along the Appalachian Trail on a fall weekend, it was easy to detour to nearby Mt. Frissell (Connecticut, 2,380 feet). Infrequent as they were, these experiences were becoming a thread running through our adventures, connecting the years in ways our “normal” hikes didn’t.

Even at this glacial pace, our “highpointing” drew notice. Most of our friends were indoorsy New Yorkers, so when Audra would tell them why we had taken an extra hour to get to the Cape, or chosen one dayhike over another, their minds turned on the concept of highpointing, and questions typically came in the same order:

“Where’s the highest highpoint?”

“Alaska, 20,310 feet.”

“What’s the lowest highpoint?”

“Florida, 345 feet.”

“Are you going to do all of them?”

“Oh, no,” I’d say, shaking my head. “It’s silly.”

“Yes,” Audra would say over me. “We’ll try.”

Nearly a decade after I discovered Highpoints of the United States, Audra and I flew to Asheville, North Carolina, to visit my brother and his family for a long weekend. The book came with us. We tagged Sassafras Mountain (South Carolina, 3,554 feet), Clingmans Dome (Tennessee, 6,643 feet), and Mt. Mitchell (North Carolina, 6,684 feet). Even I had to admit, there was something irresistible about a cluster like that. Plus, we saw peak fall colors, ate at rural diners, and poked around Cherokee-themed souvenir shops that sold skins and arrowheads. And, OK, we sacrificed actually hiking in the Blue Ridge Mountains to do it, but by this point I’d come to appreciate the way highpoints, even the drive-ups, made for fun side excursions from whatever else we were doing and introduced us to unexpected corners of the country.

On the way home from my brother’s, it occurred to me that this trip had been different: Had we spent more time highpointing than visiting? I was afraid to do the math. As if to confirm my fear, a package was waiting in our pile of mail. Audra had signed us up for a family membership in the Highpointers Club, with some 2,613 dues-paying members, plus 302 completers of all 50 states and another 589 who have done the Lower 48. ⇒

I opened the large, white envelope and pulled out the club’s quarterly newsletter, entitled Apex to Zenith. It was like lifting the lid off a secret world.

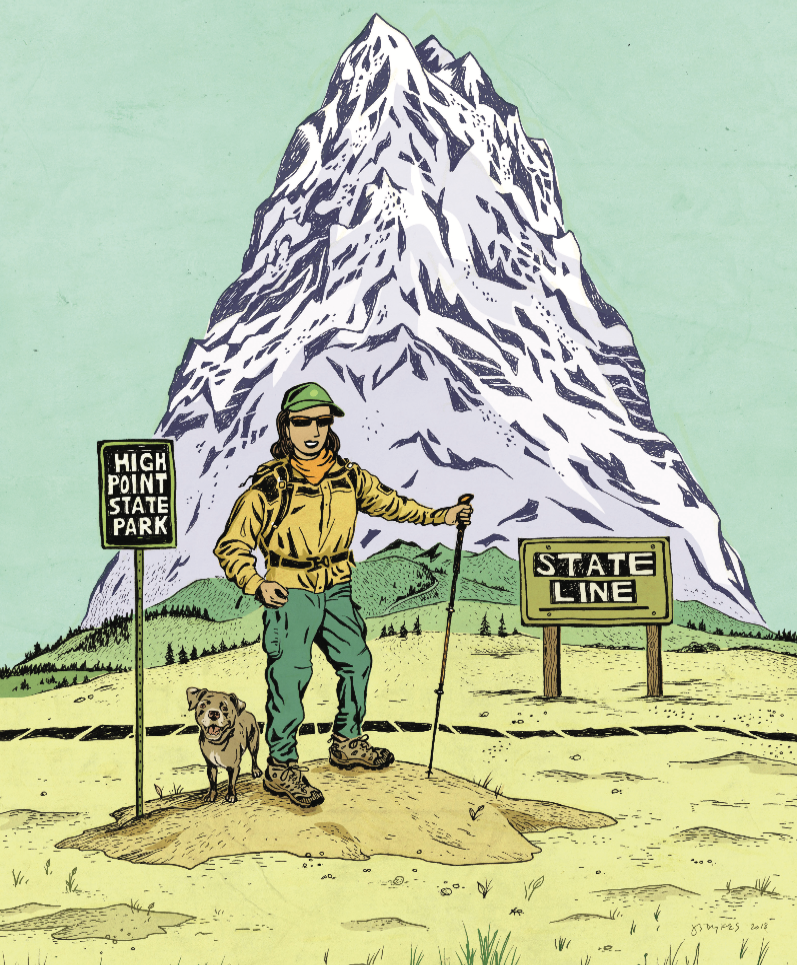

There, on its glossy, color covers, were photographs of highpointers in action: doing a headstand on the summit of Mt. Washington, kneeling next to the family dog on Hawkeye Point, posing with a 19-day-old baby on Sassafras Mountain, lying prone in mock exhaustion upon reaching for the summit sign of Cheaha Mountain. There was also a picture of helmeted climbers standing shoulder to shoulder on Mt. Hood, each raising an ice axe triumphantly. One photo showed a highpointer with an impossibly large grin—he was standing on the snowy summit of Gannett Peak (Wyoming, 13,804 feet) holding a sign that said “50.”

Every issue had a “completer’s” section of reports by those who have done all 50 or finished all but Denali, which many highpointers skip. One newsletter featured a photo of someone’s “4EVR 49” license plate.

Another installment ran a front-page photo of a gathering of highpointers at the New Jersey summit, clad in matching tie-dyed shirts—it was the annual Highpointers Convention. A convention.

Speed-record attempts. Interviews. Regional guides. Apex to Zenith was fun to read, but more importantly, it made me feel normal compared to the people who inhabited this wacky subculture. These folks were obsessed; I was just curious.

That lasted until the fall of 2010. A couple of months before, I’d lost my job in the middle of the Great Recession. Audra’s freelance career had already ground to a halt in the sluggish market—we were both unemployed. Some severance pay and savings meant we were in a far more fortunate position than many other Americans, but we were both at a crossroads. Everything was on the table: changing careers, moving to a new city, leaving behind friends who felt like family.

In the absence of knowing what to do next, one clear-cut goal presented itself: We turned to the list of highpoints. The human brain craves order, and the rest of the world felt like chaos. Looking back, it’s clear we felt like we had little else to guide us, so the list became a sort of life map.

We cashed out every single frequent-flier mile between us and headed west to knock off some of the bigger summits. We drove highways, desolate back roads, and unmaintained dirt washboard that punished subcompact rental cars. We pitched the tent, cooked by headlamp, brushed teeth with a bottle of water, hiked dusty trails, and scrambled over scree and boulders to summit markers. We studied the increasingly battered Highpoints of the United States as if it were leading us on a crusade—or at least telling us what to do next.

With book in hand, we went on a blitz: Wheeler Peak (New Mexico, 13,161 feet), Black Mesa (Oklahoma, 4,973 feet), Mt. Sunflower (Kansas, 4,039 feet), Panorama Point (Nebraska, 5,424 feet), Mt. Elbert (Colorado, 14,433 feet), Kings Peak (Utah, 13,528 feet). When we returned to the trailhead after Kings Peak, Audra pulled out the book, wrote in the date, and did a count. “You have 25,” she said. “You’re halfway.”

The milestone hit me in an unexpected way. Even though I was now unabashedly highpointing, it never occurred to me that I might actually finish someday. But now I experienced a psychological shift: I no longer thought in terms of how many I’d done, but how many I had left to do. It was like a countdown had begun.

And so the Western tour de highpoints continued. On Mt. Whitney (California, 14,494 feet), the high-altitude air seemed so oxygen-rich I felt like I could run to the top. No fatigue. No altitude headache. We felt relaxed and strong—if there were such a thing as professional highpointers, we could be part of that elite group.

After Whitney, we made a beeline for nearby Boundary Peak (Nevada, 13,140 feet). I started calling myself a highpointer. My real-world titles of “writer” or “New Yorker” had little relevance on the trail. Some days, all I wanted was to just keep going like this—mapping, driving, hiking, checking off one peak, and heading to the next.

But we knew it was only a temporary escape. Several of the remaining peaks had snow and ice hazards, and their short summer climbing windows had closed—we didn’t have the skills to climb them. And while we briefly entertained fantasies of hitting the Dakotas or blowing through the Midwest drive-ups, we were still unemployed. The cost was just too high, in dollars and in time away from job hunting. So after the three-week lark, our all-too-brief career as professional highpointers came to an end. Still, what we’d done felt like progress.

The main room of the 2012 Highpointers Convention was packed with more than 200 people—mostly men, beards mostly gray, though there were a few couples and families with kids. We were crammed into the main room of the Mazamas mountaineering club’s lodge, in Government Camp, Oregon, for the annual Friday evening social. Despite the fact that it was June, big, heavy flakes of snow fell outside.

After a couple of years, during which we’d relocated to San Francisco, started new jobs, and done a few more casual, one-off highpoints, Audra had convinced me to register for the convention. She’d read in the newsletter that a longtime club member was organizing an informal Mt. Hood climb on the side. “We’ll meet more experienced people to climb with,” she said. “This is our chance to get Oregon, and maybe prepare for other hard ones in the future.” But the snowstorm prevented a summit bid.

Instead, we tried to make the best of it at the social. Mingling in the room of strangers was easy with our common interest. Our convention badges even displayed the key pieces of information any highpointer needs to make conversation: name, home state, and completion number. Those with numbers higher than 40 typically responded with puffed chests if you started with, “Wow, what’s left?” If the number was 15 or fewer, “Just getting going, huh?” was an obvious gambit. My number, a mid-pack 33, meant that most people started instead with the home state, “California, have you climbed Whitney?” I loved the question because it led me to the story of our highpointing bender out West, and how the trip ultimately emboldened us to take the leap and move across the country.

Don Holmes, 80, author of Highpoints of the United States, looking regal with white hair, a thin smile, and a white golf shirt bearing the club’s logo, stood near the front podium. He was joined by newsletter editor John Mitchler, an Alec Baldwin lookalike. They both wore badges that said “Colorado, 50.”

Mitchler called the room to order and we settled in for the evening’s keynote about the first-ever highpoint completer, A.H. Marshall. Marshall, a wiry railroad telegraph operator with a swept-back thatch of hair and peering eyes that made him look like he was perpetually facing a gust of wind, nabbed his last U.S. state highpoint in July 1936.

Marshall began highpointing just as the U.S. spiraled into the Great Depression. He first had to create a list of state highpoints—nobody had compiled it before—which required meticulous research of conflicting sources and writing letters to dozens of Forest Service officials for different maps and advice. As a perk of his telegraph job, he got free railroad travel. So over several summers, he traveled by rail, hitchhiking, and foot—ticking off highpoints as fast as a modern-day peakbagger with the benefit of a rental car: Nevada 6/3/30, Arizona 6/7/30, New Mexico 6/15/30, Colorado 6/19/30, Utah 6/28/30.

He had no family obligations, no home to worry about. The main focus of his whole life became highpointing. In 1936, he took a multi-month leave from work in order to do his final 18 highpoints. In July, in the farm fields of Indiana, Marshall finished number 48, the last one at the time. (There, he visited three points on his maps that listed the same elevation, plus two additional areas that locals claimed were higher, just to be safe.)

Around the room there were lots of “wow, how far is too far?” head shakes. I was reminded of Stony Burk (New Hampshire, 49 at present), a living highpointer who represents the Marshall spirit. To date, he has made 423 ascents of state summits. And at 71, he continues pushing. He’s been to the Rhode Island and New Jersey highpoints in every calendar month, and climbed Tennessee’s 11 times. He’s currently helping to establish a permanent Club museum in Ohio.

All of us highpointers have sacrificed for our obsession in our own way—spending time and money, sometimes speeding through them for the sake of accomplishment, while not stopping to savor or explore arguably “better” and more wild places. On the other hand, I had one highpointer tell me that picking up the list helped him get over a divorce. It had certainly helped Audra and me deal with a job crisis. What else might our brains obsess over—breakups, money woes, the state of the world—if not for this list?

The spring after the Oregon convention, Mitchler tossed out an invitation to the Highpointer Club’s email group: He was going to be back in Portland on business, and offered to lead a climb up Mt. Hood, especially for anyone who had missed out on a summit due to the previous June’s storm. Audra and I jumped at the chance.

We had perfect snow conditions and mild weather for our ascent (number 35 for me). We took a summit photo with our small group, ice axes held high.

Back at the Timberline Lodge bar, our climbing team naturally began to talk about what was left. Audra and I shared our plans to pace out our 10 remaining Midwestern and Southern drive-ups on a couple of relaxing, stop-and-see-the-sites road trips.

A few of us were also missing three of the hardest remaining peaks in the Lower 48, and so hatched a plan to tackle them the following summer: Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. The latter’s Gannett Peak requires at least a 33-mile round-trip hike and 8,450 feet of elevation gain.

Mitchler sat back, sipped his beer, and smiled at our excited planning. I thanked him for organizing the trip. He shrugged. “I really appreciated the times when I was invited along on trips with more experienced people.”

Mitchler completed the 50 U.S. highpoints in 2003, and his obsession only grew after finishing the feat. But rather than repeating highpoints, he found new ones. He completed the county highpoints of several states and began working through the highpoints of U.S. National Parks and Monuments, and the U.S. territories worldwide (in June he completed the first-ever ascent of 3,166-foot Agrihan on the Mariana Islands, a sword grass-choked volcano that he called “the last unclimbed American highpoint”). He’s even ticking off the highest natural ground in the 50 most populous U.S. cities. “That’s neat,” he said, “because there isn’t a list—I have to map them out.” He’s done 42 of them.

For Mitchler, his multiple ongoing quests solve a common problem most highpointers face. “Almost all who finish the states say, ‘Now what?’” he explained. “Now all of a sudden you don’t have a list.”

That won’t happen to Mitchler. He told me he’s also considering a list of the highest golf courses in every state. “So far, I’ve identified 20 states and played 10 of them,” he said.

Just like the newsletter used to make me feel normal by comparison to “regular” highpointers, now Mitchler made my two decades of casual highpointing feel normal. But then I recalled the years I spent as a highpointing denier. Can we recognize when we go over the edge ourselves? Does it matter? There are plenty of people who think climbing any mountain is crazy. Who’s to say when enthusiasm becomes obsession?

On that 1,200-mile detour to the Dakotas, we went a little nuts by any objective measure. Our time on the road dwarfed our time on the trail. We skipped the Badlands and Devils Tower. Instead, we walked through what felt like a painting of the American prairie, complete with abandoned cabin and barbed-wire fence, to reach White Butte. We ran to the stone fire tower on Black Elk. And it felt like we were making each moment really count.

Now, when I look back on that road trip and other questionable itineraries, I don’t regret the places not seen. Rather, I appreciate how even my mild case of obsession has shaped how I experience the outdoors. As a backpacker, I have spent hundreds of nights out in the wilderness, hiked thousands of miles of trails—and sometimes all the beautiful places blur together. But I remember every single highpoint in vivid detail. The day, the weather, the back roads, the trail, the nearby towns, the people met along the way.

List-keeping doesn’t drive all my hikes, of course. For instance, I only recently noticed that, since moving to California, I’ve been to seven of the state’s 58 county highpoints. I’m definitely not trying to climb them all.

Loren Mooney currently has 48 U.S. state highpoints. She’s missing Virginia and Alaska.

Master the Mountains

Scramble Safer

Conquer class 3 or 4 terrain with confidence.

Assess your objective. Is it necessary or just a shortcut? What are the consequences of a fall? Don’t climb up anything you can’t climb down.

Cinch your laces. A tighter fit gives you better feel for the rock. Approach shoes and softer, stickier rubber soles improve grip.

Watch your footwork. Keep your weight over your feet for better balance. Paste your soles onto low-angle rock to maximize surface area. Dig into small, flat holds with the inside of your big toe, and flex your calf to press down and into the wall.

Maintain three points of contact. Move slowly, and test holds before weighting them.

Be suspicious. Look for fissures around blocks, which can mean they’re detached from the rest of the formation. Knock on thin, flake-like holds. Hollow? Don’t touch; they could snap off.

Get an alpine start. Weather risk and warming snow can make an early start critical. Don’t blow it.

Set two alarms. Hitting snooze is a good way to sleep through your wakeup window.

Pack the night before. Get your kit ready to grab and go. Do all your snack and breakfast prep before hitting the hay.

Get dressed. Lay out everything you’ll hike in. Better yet: Sleep in your clothes.

Caffeinate. If coffee is a necessity, use instant and make sure you allow time for boiling water.

Eat on the go. Choose breakfast foods that require no dishes (oatmeal in a packet is a good bet), or eat cold snacks while hiking.

There’s a List for That

Got summit fever? Here are just a few of the checklist challenges around the country.

50 State Highpoints

The Highpointers Club site has an online guide and store, and a blog with club news and membership info.

County Highpoints

Arguably the most obsessive peakbagging faction, the County Highpointers Association hosts an interactive map with established and debated county highpoints for each U.S. state, plus more peakbagging esoterica.

Colorado 14ers

In addition to the Fourteener records, the Colorado Mountain Club maintains an online register, MySummits, where you can log your progress on Colorado’s top 100 peaks.

South Beyond 6,000

The Carolina Mountain Club recognizes those who summit 40 peaks over 6,000 feet in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia.

New Hampshire High Peaks

Since 1957, the Appalachian Mountain Club has charted hikers’ progress on the 48 4,000-plus-foot peaks in the White Mountains, with special awards for those who climb in winter. The club also keeps lists for New England’s 4,000-footers and 100 highest peaks, as well as the 111 4,000-footers of the Northeast.

Adirondack 46ers

More than 10,000 completers have registered their climbs of the Adirondacks’ 46 highest peaks since the list began in 1925.