The Japanese Monk Who Hiked a Mountain for 1,000 Days

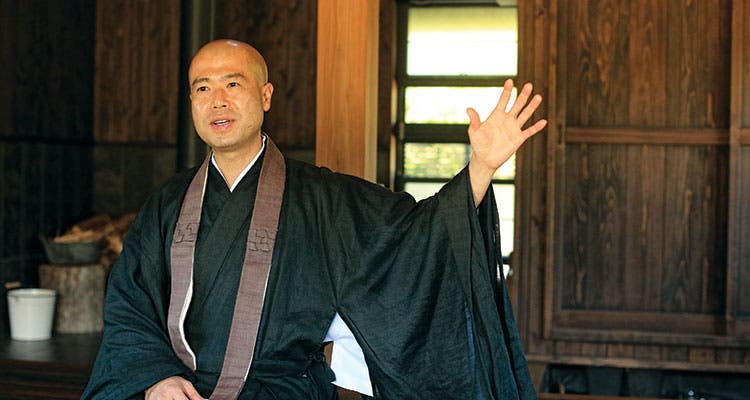

'Photo by Stephan Repke'

The route up Mt. Omine, in southern Japan’s Yoshino-Kumano National Park, climbs more than 4,000 feet in just under 15 miles. The route is so steep and rocky it has wooden stairs and ladders, ropes, and even chains to assist with the ascent. A round-trip journey demands about 16 hours of continuous movement—even for fit hikers.

Many trekkers might turn back during such a challenge, and there would be no shame in that. But Ryojun Shionuma is no ordinary hiker.

When the Buddhist monk joined other pilgrims on Omine, he was not interested in a single life-list visit to the seventh-century temple on the summit. He had taken a vow to complete a sacred, thousand-day challenge, climbing Omine every day from May to September for nine years in a row. It was an audacious undertaking, to be sure, but among monks the Thousand Day Circumambulation is considered a kind of shortcut to enlightenment.

Buddhists have been seeking more efficient ways to what’sknown as bodhi, or “waking up,” for more than 2,000 years. Usually, a lifetime of meditation is involved. But a small Japanese sect had developed a unique approach dubbed “circling the mountain.” That is, hiking. Could the trail actually be the quickest path to Nirvana?

However, this shortcut has a catch. Once Shionuma took his vow, he was obligated to finish, regardless of fatigue or injury or weather or second thoughts. Typhoons would devastate the trail with heavy rains and winds; gusts would blow out Shionuma’s traditional Japanese lantern, which he relied on during the several hours of darkness he hiked in each morning. He also faced venomous snakes and wild boars and bears. And he always made the journey alone.

But at least he didn’t have to see the graves of other monks who had failed in their thousand-day shugyo (“austere training”). Shionuma had chosen Mt. Omine for his quest because it’s where the practice originated in the seventh century, and it’s harder and more remote than Mt. Hiei, where the ritual moved shortly after its inception. On Mt. Hiei, trails are sprinkled with the graves of monks who failed, either expiring from injuries, stopped by the elements, or by way of ritual suicide. After the first 100 days, a monk who is unable to complete his practice must choose between disembowelment and hanging himself with his “safety” rope. (This code of discipline is unique to the Tendai monks, who have brought a strict sense of honor to the ritual.)

Only once, after passing out, having lost more than 20 pounds from illness, did Ryojun Shionuma think, as he came to, “I will have to apologize to Buddha and kill myself.”

Fewer than 50 monks have completed the Thousand Day Circumambulation in the last century and a half. Originally, however, the practice was not quite so difficult. It started with a mountain priest named En-no-Gyoja, who, in the late 600s, meditated for a thousand days on top of Mt. Omine, where he lived in caves and huts and survived off the land. He was following Buddha’s teaching that “training oneself by repeating the same practice with passion can lead to enlightenment.”

Later, a follower of Gyoja interpreted the teaching to mean a thousand days of running around the grounds of the temple that was built on top of 5,600-foot Omine. He was the only one who completed this Thousand Day Circumambulation on Omine before the practice migrated to Mt. Hiei, outside of Kyoto. There, Tendai monks established the ritual known today. They became known as the “Running Monks” or “Marathon Monks” of Mt. Hiei.

The Tendai tradition specifies a very detailed plan, run-hiking a thousand days in 10 segments over the course of seven years. The practice starts “easy” with 19-mile days and culminates, in the final year, with a segment requiring 52-mile efforts—a full daily double marathon for 100 straight days. En route, monks pause at more than 250 worship stations. The journey is eased, to use the term loosely, by rotating “pushers” who help propel the monk forward by applying gentle pressure with a padded pole placed against the small of his back.

And that isn’t even the hardest part. At the end of the thousand-day challenge, monks take on the doiri, or nine straight days of “Four Nothings,” during which they go without food, water, sleep, or reclining for nine days. Midway through, dehydration becomes so severe that the monks’ inner cheeks begin to adhere to themselves—then they are allowed to rinse their mouths with water but must spit back every drop.

On Omine, Shionuma planned to complete his own version of the ritual, doing continuous 30-mile days during each hiking season for nine years—plus the Four Nothings. If he finished, he would become the first person to do a Thousand Day ritual this difficult.

There’s good news for those of us who don’t have Shionuma’s determination and time. New research suggests that hiking and meditating, when combined, might help us achieve our own personal Nirvanas.

Many studies have shown the positive mental effects of both meditation and exercise. Researchers at Rutgers University wondered if the two, practiced together, might intensify the outcome. The resulting study, published earlier this year in Translational Psychiatry, showed the effect was “robust.” After just eight weeks, participants reported being happier and they had measurably better concentration. Subjects who had started the study with depression had a 40 percent reduction in symptoms, and tests showed brain cell activity in their prefrontal cortex that was almost identical to that of the subjects without depression. Why the profound effect? Researchers proposed, “Theoretically, the combination of aerobic exercise and focused-attention meditation may increase the number of newborn cells in the hippocampus and rescue these newly generated cells, which may be integrated into the brain circuitry.” Translation: Mindful exercise is very, very good for your brain.

Of course, many endurance athletes don’t need a study to be convinced there’s a link between mind and body. Terri Schneider, author of Dirty Inspirations: Lessons from the Trenches of Extreme Endurance Sports, suggests that, without perhaps being conscious of it, ultra-endurance athletes are chasing a monk-like experience. They seek discipline on the trail because the routine removes the clutter and chatter of “normal” life. “The repetition of moving forward for extended periods strips away everything until our focus becomes … moving forward,” she says. “We become hyper-present.”

But most of us have limited time—work, family, and other obligations occupy everyone but monks and thru-hikers. Fortunately, you don’t have to rent out the house and hit a long trail to benefit from this powerful combo. Subjects in the Rutgers study spent only an hour twice a week at the task, splitting time between meditation, exercise (on a treadmill or stationary bike), and walking meditation. Shionuma says that many forms of exercise will work; they just need to be repeated, the same way.

When he was a child, Shionuma’s mother and grandmother often took him to visit temples and shrines, telling him to help other people and be a positive person. (His father was a drunk, he says, and his parents divorced when he was 12.) His mother suffered from heart disease so she couldn’t work, and neighbors helped to feed and raise Shionuma, and in so doing reinforced the lessons about aiding others.

Those formative experiences made Shionuma’s young mind ripe for a television program about the Tendai Buddhist practice. After watching it, he says, he knew he wanted to commit to the severe undertaking. It sounds implausible—a TV show?—but Shionuma insists he can’t find any motivation beyond what he learned as a child, and the show convinced him that this was the best way to learn how to serve others. “That’s it,” he says. “It is purely only one reason.” Though he admits no one else shared his confidence, especially because he wasn’t a strong kid. “As a sickly fifth-grader, I told my parents what I wanted to be when I grew up. They laughed at me.”

At 19, Shionuma started down the path to becoming a monk, and after a relatively short four years of training, in 1991, he decided he was ready to take on the thousand-day practice. But he surprised even other monks by opting for Mt. Omine, where the practice first began. However, where the original monk had done a circumambulation around the temple, Shionuma chose to climb the mountain from bottom to top. If he finished, he would become the first to do it as an ascent.

He consulted the only living monk who’d completed the ritual (on Mt. Hiei), who told him he thought Omine would be too hard. Shionuma wasn’t dissuaded. He appreciated the repetition that the single trail up and down Omine offered, in contrast to the variety of routes taken by the monks of Mt. Hiei. Shionuma also embraced the solitude and lack of pushers. “I was fueled by Omine,” he says.

That doesn’t mean it was easy. He began each “day” rising at 11:30 p.m. and purifying himself in a waterfall. He spent about an hour preparing and dressing himself in traditional robes made of hemp, then topped it with a cedar-woven lotus hat. Shionuma’s wardrobe and supplies—which included a suicide knife and rope—weighed about 15 pounds. He wore split-toed tabi socks with rubber bottoms (traditional woven sandals wouldn’t withstand Omine’s rough terrain). He set off from the temple at 12:30 a.m., covering much of the daily journey in the dark.

During nine years on the mountain, Shionuma says there were very few days when he felt good. “There was almost always something to trouble me, whether it was knee, heart, headache, etc.,” he says. Just a month into the attempt, Shionuma lost his toenails and fingernails. Later in the first year, he dealt with blood in his urine from kidney problems. He had to care for himself, as he couldn’t take a break from the mountain to visit a doctor. “You press forward dispassionately, feeling as if you are immersed in suffering,” he says. “When you do that, the mind gradually becomes very clear.” It was only once, after a bout with the flu, that he passed out and, as he came to, thought he might not be able to continue. “But then I remembered my childhood dreams and found the motivation to continue on with my quest.”

In the beginning, Shionuma saw ghosts and scary images along the trail. Later, in the intermediate periods, he was treated to beautiful visions. And during the final stages of his thousand days, Shionuma didn’t see anything but reality. He focused on his form and breath. He repeated a mantra with every step: “Humility” (one step), “Pure mind” (one step). He finished hiking in 1999, and completed the Four Nothings the following year.

Did it work? Did he achieve what he sought?

Shionuma answers cryptically. “Do you remember when you first learned to ride a bike and you ‘got it’?” he asks. “That feeling of ‘getting it’ where you are balanced and moving freely, gliding along with joy; that is Nirvana.” He says the thousand-day ordeal taught him gratitude, self-examination, and consideration for others—and enables him to teach compassion and humility the way he envisioned as a child. “The reason that I had a full, satisfied heart during my solitary ascetic practice might be because I felt affection for even the trees and the insects,” he says.

He still returns to Omine once a year to remember what he’s done. He ascends and descends alone because he always did it alone. At his resident temple near Sendai, he enjoys his peaceful daily life of praying, gardening, and living close to nature. He travels occasionally to give talks and invites others to visit him so that he may spread his message. “There is valuable meaning in doing the same things, in the same way, and as devotedly as you can,” he says. “If you do this, the Way will most assuredly open up.”

And he still runs three or four times a week, but only about 6 miles, wearing normal running clothes. “I’m not a strict guy,” he says with a smile.

Adam W. Chase is an ultrarunner based in Colorado. His longest race to date was seven days; he did not meditate.