Desert Survival Basics

'Expect extremes in the desert. (Shane Thais Hillyard)'

Expect extremes in the desert. (Shane Thais Hillyard)

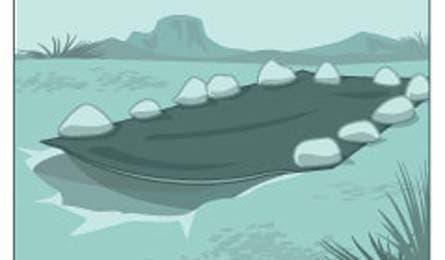

An insulating, life-saving desert shelter. (Supercorn)

Hydration 101

According to NOAA, heat is the number one weather-related killer in the U.S., accounting for 162 deaths annually. A person just sitting in the shade on a 90°F day for 24 hours will lose a minimum of six quarts of water (through perspiration, urination, and respiration), reports the Department of Defense. And hikers? Here’s what happens:

What you lose Depending on fitness and conditioning, the average person sweats 27.4 to 47.3 ounces per hour while exercising, says Stacy Sims, PhD, an exercise physiologist and nutrition scientist at Stanford University. For a 155-pound hiker, that’s 2 percent of your body water. Lose that, and you’ll also sacrifice 11 percent of your VO2 max—your body’s ability to take in and use oxygen—significantly reducing your cognition and reaction time.

What to put back Pack 2 to 6 quarts of water per person, per day depending on the length of your trip—more if you can. But water alone won’t work. Drink too much without replacing electrolytes and you can suffer from life-threatening hyponatremia. So, each hour, suck down at least two 16-ounce bottles of water with a drink mix with 150-200mg sodium and at least 50mg potassium. Try products from GU (guenergy.com) or Vitalyte (vitalyte.com).

Be prepared One reason hikers get into trouble: They don’t realize how temperature and humidity combine, making conditions more severe than the thermometer suggests. Use the heat index—which is geared toward slightly lower-exertion exercise than backpacking—to get a real measure of what you face.

—-Hazards

Things that sting The golden rule of desert living? Look before you step or touch, and you’ll avoid surprise encounters with rattlesnakes, scorpions, and spiders. Check your shoes, sleeping bag, and anywhere you’re about to sit. If you’re stung by one of the more venomous breeds—like a brown recluse spider or black widow—reduce swelling by keeping the limb cold, then get to a hospital as soon as possible. The most incidents? Africanized bees found in the Southwest. They’ll attack with little provocation when you’re in their territory. Pull your shirt collar tight up around your neck. And run. Carry Children’s Fastmelt Benadryl (or an EpiPen if you have a history of anaphylaxis) in your first-aid kit.

Flash floods In the Grand Canyon, 80 percent of flash floods happen between noon and 8 p.m. during the monsoon season from July to September. Check the weather and avoid narrow canyons during the rainy season. If water rises and runs faster or muddier, get to high ground. Stuck? Find a wall or boulder to protect your body from debris. If you’re carried off, keep your legs in front of you with bent knees.Essential GearCover up to keep cool. Think like a cowboy. Stay clothed to cut down on evaporative sweat loss, and you’ll increase survival time by 25 percent. You’ll need a brimmed hat, sunglasses, a soaked bandanna around the neck, sunscreen, and breathable clothing (poly/cotton long-sleeve shirt, lightweight nylon pants, wicking wool socks), and lightweight, durable boots. See boot reviews on page 42. Pack binoculars for scouting for water and consider a lightweight umbrella to shield you from UV rays.

—-

When Water Runs Out

STAY IN THE SHADE

In a survival situation, stay out of the sun from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and hike only during the cooler hours of the evening or morning. Lost hikers have lasted up to two days without water in the triple-digit heat of the Grand Canyon and Death Valley, while others, trying to find water in the middle of the day, have perished within three hours. Hole up in the shade like a coyote, conserve your precious sweat, and await rescue.

WHERE TO FIND WATER

Forget solar stills or dowsing, and don’t assume that the creek, spring, or waterhole marked on the map is going to exist this year. Talk to locals like rangers or ranchers in the area and find out what the water conditions are really like. Then make sure you know how to find it by reading the subtle clues written across the terrain.

Tree cavities and hollows Look for water-loving trees that stand out in the desert. Willows, cottonwoods, and sycamores, with their bright green leaves, can be seen from miles away and are often signs that water is close to the surface. It may be visible or you may have to dig down a few feet at the tree’s base. Use a bandana to absorb puddles.

Tinajas Spanish for “earthen jars”—ranchers just call them tanks, as in water tanks—these are rock depressions where water can be found by the gallons, if the rains have been good. Scope out the landscape from above with binoculars, and look for distant shiny spots and the presence of bright green foliage. Often, you can find tinajas near petroglyphs left by the Native Americans whose lives depended on them. If you camp near a tinaja, don’t contaminate it. For many animals, it may be the only source of water for miles around.

Cacti: Eat Me, Drink Me?

Drink

Think slicing open a juicy barrel cactus will yield a quenching cup of water? Nope. There’s no water inside, and due to the alkaloids, most people will experience cramping and vomiting, which aggravates dehydration. The fishhook barrel cactus isn’t completely toxic, but it can still cause diarrhea. In an emergency, suck on its inner flesh.

Eat

Prickly pear cactus fruits won’t replace the water your body needs, but they’ll help quench your thirst. They’re sweet but heavy with seeds and can be collected in late summer. Remove the stickers or glochids and peel the skin or char it in fire coals.

Navigate

Find north Use the stick-and-shadow method: When the sun is casting shadows, place a three-foot stick vertically into the flat ground. Clear the area around it of debris. Mark the tip of the stick’s shadow with a stone. Wait for at least 15 minutes and mark the end of the shadow again. The line connecting the marks roughly coincides with the east-west line. A line perpendicular to this line through the central stick indicates the north-south line.

Stay on track Navigating featureless desert terrain without a GPS? Good luck keeping a perfect bearing. Instead, “aim off” your destination by 10 degrees with your compass. Instead of heading directly toward your target, alter your bearing by 10 degrees for distances up to a mile and five degrees for greater distances. For example, let’s say you’re trying to reach your car. If you aim to the left of it by five degrees, when you reach a line parallel to your desired location—like the road—simply turn 90 degrees to find it.

Build a Shelter

In the Sonoran Desert near Tucson, the temperature once plummeted from 120°F during the day to 34°F at night. Lesson? Find insulated shelter. First, look for caves or natural features in which to hunker down. No luck? Construct a makeshift cocoon. Dig a body-size trench and line the rim with large rocks; cover it with a folded tarp or emergency blanket. The rocks will help secure the blanket and prevent the sides from eroding. Insulate the bottom with extra clothes.

—-

Signaling For Help

Choose a quality mirror like Coghlan’s 2” x 3” Signal Mirror ($10, coghlans.com). The glass has greater candle power and sheen than a polycarbonate mirror, and its flash can be seen from 50 to 100 miles away, depending on weather conditions. Take your hat off to prevent the brim (or its shadow) from obscuring the front surface area of the mirror, place the sighting hole in the middle of the mirror up to your eye, and tilt up (so you are not looking directly at the sun). You will see a small bead of white light. Next, direct this bead of light over to the search plane or distant rescuer and “flash” them three times. Patterns of three are the recognizable universal distress signal. When not actively signaling, hang the mirror from a tree near your shelter—searchers could spot the reflection as the mirror turns in the breeze.