Prof. Hike: The Instinctive 127 Hours

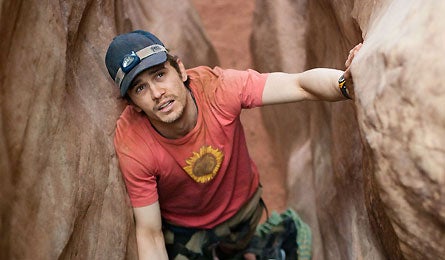

'Could not thinking too hard help you survive like Ralston? (Chuck Zlotnick)'

If you haven’t seen 127 Hours, the movie adaptation of Aron Ralston’s survival story, keep reading this post. But once you’re done, go see it. Not since the church fresco scene in The English Patient (1996) has a Best Picture-nominated film depicted such creative climbing rope and harness work.

I’ll assume you’re familiar with Ralston’s 2003 ordeal. If not, here’s the official eight-word synopsis: Canyon, rock, stuck, five days, multi-tool, tourniquet, fame. This post isn’t about whether Aron Ralston is a hero or a dunce. Heck, he’s already admitted he made boneheaded mistakes in his bestselling book. And now those blunders are the subject of a blockbuster movie. How many of us would welcome that level of attention to our own hiking missteps?

And while most of us claim we wouldn’t make the same poor choices that led Ralston to his five-day jam, it’s equally true that, if trapped like him, most of us wouldn’t have lived, let alone returned to hiking, climbing, and skiing with only one arm. Countless solo hikers who faced similar odds ended up dead. Many of their stories have appeared in Backpacker, including John Donovan’s 2005 disappearance on Mt. San Jacinto and Mike Turner’s 1998 entrapment by boulders in Wyoming’s Wind River Range.

What made Ralston’s outcome different? A sheltered canyon? Yes. The ability to self-amputate? Certainly. His lucky encounter of rescuers soon after freeing himself? Probably vital. But Ralston needed something more. Most of us could tolerate 24 or 48 hours in a similar spot. But to endure the full 127 hours, Ralston needed his hidden survival instincts to kick in. Here are three of those instincts, and how they kept him alive.

1) Inventory Your Gear

Wait. Organizing your gear isn’t instinctive. It’s intentional, right? Perhaps, but consider what happened in Blue John Canyon. Half an hour after getting stuck, Ralston was still amped with angry adrenaline, he’d drunk one-third of his remaining water, and his brain veered toward dire, profanity-laced conclusions. Then he stops and slows everything down by emptying his pack and placing each item on top of the boulder that trapped him. Two bean burritos. A CD player (after all, this was 2003). An LED headlamp. A cheap multi-tool, and so on.

The methodical act of inventorying his gear altered his entire situation by slowing his breathing, focusing his mind, and improving his outlook. No longer was Ralston thinking about dying. Instead, he began brainstorming all the ways he could use his gear to survive. So the instinct I’m referring to here wasn’t the act of organizing—it was how his mind and body responded to this methodical, rationale process. The same calming effect can occur when—after the initial panic of realizing you are hopelessly lost—you stop moving, sit down, add a layer of clothing, eat and drink, and consider your options.

2) Rely on Routines

Boredom can kill. Just ask anyone who’s sat through a kid’s piano recital. Except recitals rarely exceed three hours. Ralston’s ordeal lasted 127 hours. What do those hours feel like? Well, if you sat down at your desk on Monday at 9 a.m., it means you couldn’t visit the water cooler until 4 p.m. on Saturday. Heck, even Microsoft Solitaire loses its appeal after three days.

To cope with his isolation and boredom, Ralston relied on both natural and artificial routines. Like organizing gear, following routines isn’t instinctive. What is automatic, however, is our hunger to create them. Schedules, rationing, and predictability enable us to function better in chaotic situations. Studies prove that humans deprived of normal light-and-dark cycles are more stressed, less alert, and suffer more medical ailments.

Natural routines are easy; you just need to notice them. Two that are beautifully depicted in the movie are the 15-minute burst of sunlight that warmed Ralston’s body every morning, and the punctual raven that overflew his canyon prison each day. With little else to remind him of the outside world, these dependable events got him through the nights.

Ralston’s self-made routines were even more essential. Within an hour of getting trapped, Ralston began chipping at the boulder with his multi-tool. Even after these efforts showed little progress, he continued to carve away. Attacking the rock, he wrote, kept him active, moving, and warm. Plus, it eventually convinced him that dramatic action, like amputating his arm, was his only hope for escape. To ration his water and food, Ralston adopted a strict eating and drinking schedule tracked by his digital watch. And at one point he decided to call for help only once a day to reduce his anxiety and panic.

You can transfer Ralston’s food, water, and “staying warm” routines to any survival situation. Other routine tasks for lost hikers could be blowing a rescue whistle every hour, calling 911 from prominent ridgelines and peaks, singing songs, and periodically checking for signs of hypothermia.

Continue to page 2…

3) Daydream Away

Interspersed throughout the book and the movie are Ralston’s daydreams about water, food, past loves, previous adventures, and his family. With nothing else to do, remembering became his primary recreational activity. And unlike his “Oh my God, I’m gonna die!” thoughts, casual daydreaming actually helped him stay focused and alive. In fact, it took visions of his yet-to-be-conceived son—a blond three-year-old boy in a red polo short—to propel the delirious Ralston to finally break his arm bones and slice through the flesh. The purpose of dreaming is to organize our memories—to determine which ones to keep, which to discard, and which mean the most to us. In stressful situations, daydreams naturally occupy our brain with warm, positive, and encouraging images.

I’ve never tried to amputate my arm, but I’m a pro at daydreaming. Ten years ago I worked on a sheep farm in the Borders region of Scotland. My job was to care for 400 pregnant ewes and deliver their newborn lambs. But when the sheep we’re giving birth, I spent most of my 16-hour days standing around letting my mind wander. Like Ralston, I relived past memories, dissected old conversations, and vowed—given the chance—to fix the mistakes I’d made. By the time my two weeks on the farm finished up, I didn’t feel reborn like Ralston, but I did sort out a lot of personal history.

Is survival instinctive or learned? Or what lessons did you discover in 127 Hours? Post a comment, or send an email to profhike@backpacker.com.

—Jason Stevenson

Jason Stevenson is the author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Backpacking and Hiking