Backcountry Fly Fishing Is Easier Than You Think

(Photo: Thomas Juul via Getty Images)

There’s nothing better than spending a day casting lines over a river and feeling the push and pull of fish on the other side. This is not just for expert anglers; beginners can pick up fly fishing as well. Watching what goes on underneath the water makes you feel more connected to the backcountry, too. With these tips, you’ll be reeling in fresh-caught dinner in no time.

Master the Overhead Cast for Fly Fishing

Just like golfers have many different types of swings, anglers use various fly-casting techniques. Beginners only need to learn this one.

1) Find the best spot.

Fish in high-mountain headwaters are stealthy and skittish. They hide from predators (like hawks) beneath undercut banks, in deep pools, and in the eddies of submerged rocks and logs, which also provide respite from pushy currents.Walk at least 6 feet from the water’s edge. Tracking any closer creates vibrations that put fish on high alert. Mind your shadow. Backlight makes fish spotting easier, but casting a silhouette onto the water scares them into hiding.

2) Create enough space.

Beware of line-tangling trees and bushes—standing away from the shore ensures a snag-free back cast. Ensure that you have at least 20 feet of clearance above and behind you before casting. Standing in the water affords plenty of room to avoid tangles with trees and makes it easier to spot trout.

3) Prep the line.

Pull about 20 feet of line from the reel and out the tip of the rod. Lay or toss the line on the ground or in the water directly in front of you so that it will easily lift in the air when you cast. Arranging it in a straight line will allow it to lift more easily.

4) Load the rod.

Hold the rod with your dominant hand. Point it forward, parallel to the ground, and grasp the line near where it emerges from the reel with your other hand. Keeping your casting elbow tucked into your side, pull the rod powerfully behind you at 45 degrees from your body. Stop when your casting hand is in line with your shoulder (at 2 o’clock on an imaginary clock on your casting side, or 10 o’clock for left-handed casters). As the rod flexes, the line will swing backward, tighten, and form a loop with the fly behind you and overhead.

5) Pause.

Wait a fraction of a second while the energy from the rebounding rod transfers to the line, causing it to form a loop. It can be helpful to look behind you to watch how the rod loads. If you don’t pause, the rod won’t transfer energy to the line, making it impossible to cast the fly forward. If you wait too long, the fly will hit the ground or water behind you.

6) Cast forward.

Smoothly hinge your arm forward, stopping at 10 o’clock (2 o’clock for lefties). Keep your wrist rigid; power comes from the forearm. The line and fly will fling into the water in front of you. Drift your fly down currents that skirt fish hangouts instead of fast, midstream ones. Allow your casting arm to relax into a comfortable position as the fly lands. Cast across and upstream to keep your line from landing directly above fish and spooking surface dwellers.

7) Practice.

Try false casting to improve muscle memory and timing: Keep the fly airborne while continuously casting between 10 and 2 o’clock, allowing the line to swing back and forth without landing. “Explore for productive water. Natural obstacles segregate fish,” says fly fisher Kelly Bastone. “Some river stretches will be empty while others teem with trout.”

8) Fool the trout.

When targeting a trout in moving water, cast a couple of feet ahead of it in the direction it’s facing (typically upstream) and drift the fly over the fish. In flat water, don’t let the fly sit still for more than 20 seconds. Twitch the rod and line so that the fly imitates a real insect.

Know Your Flies

Fish eat bugs. Your task is to use artificial flies that mimic the real deal. They weigh next to nothing, so pack as many as 20 of varying types because you’ll inevitably lose some flies to trees and bushes. Your local fly shop will have good regional beta, but all complete fly boxes include these four basics.

Parachute Adams

This fly is a staple for trout fishing because of its resemblance to a wide range of insects. It imitates a mosquito, caddis, mayfly, midge, or horsefly.

Elk Hair Caddis

Fishing a swift, rocky river? This variety mimics the caddisfly, which lives in those areas, and comes in brown, gray, olive, or tan to match the local hatch.

Dave’s Hopper

This fly imitates a grasshopper, and fishes best near the bank during summertime, when terrestrial insects are abundant.

Griffith’s Gnat

This smaller fly imitates many different insects, including the winged ant. To a trout, it can look like both a cluster of midges or a single adult midge.

Read the Water for Fly Fishing

Knowing where the fish hang out in a river or lake is just as important as the cast. During insect hatches, trout rise to feed, creating hundreds of dimples on the water’s surface. Trout seek out food-rich zones and avoid fast currents, which require more energy than still water. Wear polarized sunglasses to spot trout underwater—and protect your eyes from wayward hooks. For best success, cast your fly in the following spots.

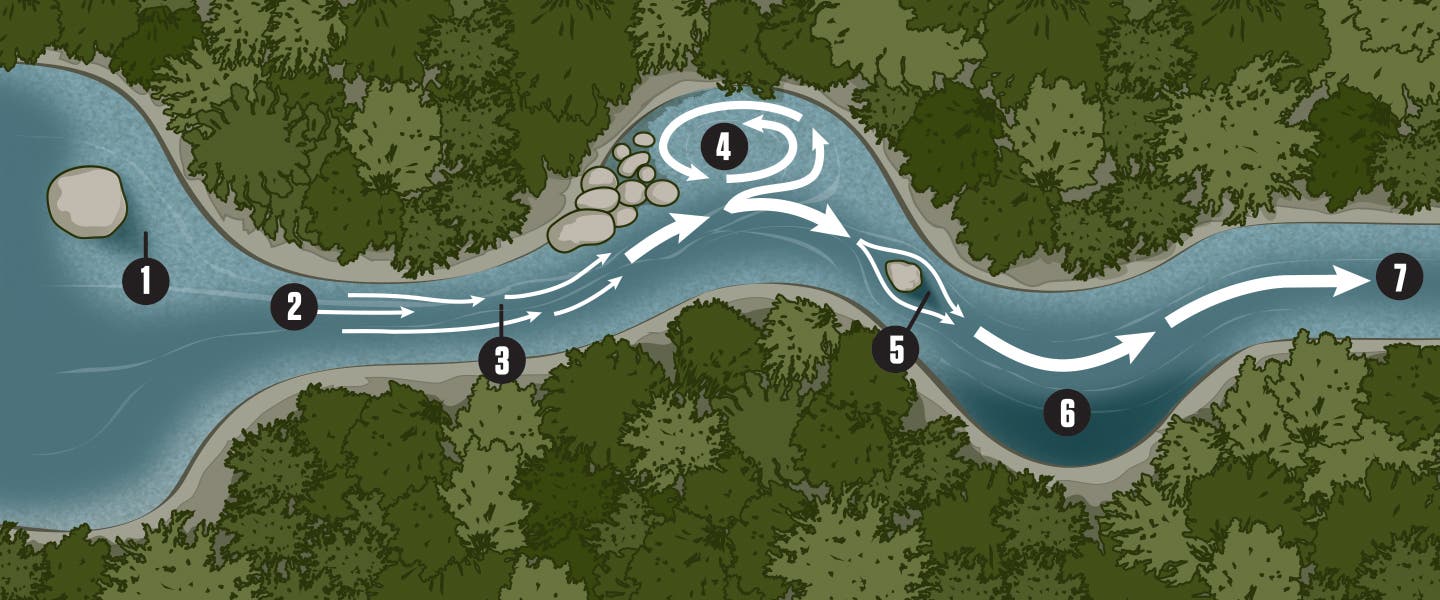

1. Structures

Large rocks or dropoffs in the still water of lakes and ponds often hide trout, which are attracted to the cooler water here.

2. Inlets and outlets

Food sources are concentrated where the water enters and exits a lake. Spawning occurs in outlets from still water sources, making it a great place to cast your fly.

3. Seams

Fish await food in the current boundaries between fast-moving and slower-moving water. Recognize a seam between currents by the lines on the water’s surface.

4. Eddies

Insects get stuck in areas of a river where the water flows upstream in a circular motion; currents are slower here, which fish use to their feeding advantage.

5. Pocket water

In moving water, the slower flow downstream of a large rock often conceals trout watching for food in the faster current.

6. Pools

Deep, slow-moving areas in the river attract trout for their lazy currents and cool temperatures, especially in warmer bodies of water.

7. Runs

Fish tend to rest in long, straight-flowing areas of water defined by a channel, waiting to nab food floating by overhead.

Be Aware of Safety Hazards

I was fly fishing Colorado’s South Platte River one summer afternoon when a thunderstorm blew in. I left the river (most fly rods are made of conductive materials, so the last thing you want to do is wave around a lightning rod while standing in water), but instead of hiding in the trees, I decided to hike a mile back and wait out the storm in the car. The thunder sounded distant; I thought I could make it.

I walked at a brisk pace and concentrated on holding my fly rod in my left hand parallel to the ground to keep a low profile. Suddenly I felt a sharp pain in my left elbow. I chalked it up to “old guy pains” and kept walking. Thirty seconds later, I felt an even sharper pain in my left arm and looked down to see all the hair on my body standing on end. The storm was directly overhead and I could feel the electricity in the air. I threw my rod on the ground and ran for the trees. I hadn’t been running more than two seconds when the lightning struck 100 yards away. Fly fishing can be absorbing; remember to look up as well as down.

Yay! You feel a pull. Now what?

“Forget the net,” Bastone says. “High-mountain fish are small enough to reel in without one.” Keep the fight in open water by positioning yourself between your catch and features (like strainers and logs) where it may try to seek refuge. Follow your catch downstream. If it takes off, the fish’s fight combined with the water’s pull might snap your line. Keep the tip up so you maintain a slight bend in the rod to distribute tension along the entire line. A straight rod stresses weak points: the end knots and tippet.

Check local regulations before harvesting a trout; catch and release is standard. If you’re setting your catch free, reel quickly to avoid fatiguing the fish, and keep it in the water while you retrieve your hook.

Cooking Trout in the Backcountry

In a spot where keeping your catch is allowed? Have ’em for dinner. Backcountry fish are smaller than their frontcountry kin, so filleting can be impractical. Cook them whole and add a dusting of salt and pepper for a gourmet campfire meal. Pack a pocketknife or multitool with a blade at least three inches long. For the best taste, cook trout within two hours of catching and killing them. Bastone offers some tips on cooking on your catch in a safe, delicious way.

- Dispatch the fish with a fast blow to its head and rub vigorously in a stream to remove the natural slime layer. Don’t sweat the scales; cooked skin slips easily from the flesh.

- Small trout (less than 12 inches) are best gutted and cooked whole. To gut the fish, slice its belly from the throat to the front of the anal fin. Cut the skin and flesh only, leaving entrails intact. Make a second cut below the jaw, perpendicular to its spine. Grasp the loosened jaw and pull (with attached innards) toward the tail. Scrape out the bloodline.

- Large fish (12-plus inches) are gutted differently. Hold the knife parallel to the gill, and slice down to (not through) the backbone. Pivot the blade so it faces the tail and cut along the backbone. Leave the fillet attached to the tail, turn the fish over, and fillet the other side. Cut off the tail and remove any small bones in the fillets.

- Brush with olive oil and pan fry, covered, over medium heat. High heat burns the exterior before the inner meat can cook. When the flesh flakes with a fork, it’s done.

- Where bears are a concern, carry entrails and bones at least a half-mile from camp and bury them in a cat hole. Wash your hands thoroughly and change out of your cooking clothes, which should join food in bear-proof storage. In a bruin-free zone: Play by the LNT book and double-bag fish waste to pack it out.

Originally published in August 2011; updated in November 2021