Killer Hike

'On farmland in eastern Washington. '

Hunting is the act of hiking with a bomb in your hands.

The thought runs through my head as I walk across a stubbled wheat field on a freezing October morning in eastern Washington. I’m in the Palouse, a land of gently rolling bluffs and prairies. The land here unfolds in sensuous dips and swirls, like the topography of a bell pepper. In farming circles, the topsoil under my boots is legendary. A good man with a tractor can grow 75 bushels of wheat an acre, twice what the dirt yields in Kansas. Nobody’s plowing or harvesting at the moment, though. It’s opening day of deer season. Every farmer in the county—or so it seems—is duded up in a blaze-orange vest, rifle in hand, looking to bag a buck.

I’m here on the same mission. I’m wearing the orange vest, the camo cap, and the two-day growth on my chin. I’m toting a Ruger .270, and in my pocket is a permission slip from the state of Washington that allows me to fire it at properly antlered ungulates. I am, for this day at least, and for the first time in my life, a hunter.

“We’ll check out this dry creekbed,” Jennifer says, whispering just loud enough to be heard over the sound of our boots crackling the wheat remnants. “But stay low on the hill. Be careful not to skyline.” Skyline, a verb: To allow one’s silhouette to appear over the crown of a ridge, spooking potential game.

Jennifer Brenner is my mentor. She’s a farm girl raised nearby, and a hunter since she could walk. Brenner, 42, is one part naturalist, one part park ranger (her day job), and two parts Gretchen Wilson. Deer hunting at dawn? Hell yeah!

Nothing flushes from the creek, so we raise our binoculars and glass the hillside across the valley. “I see three over by the eyebrow,” says Brenner. “They’re bucks.”

Eyebrow? I have no idea what she’s talking about. I scan until I see something vaguely deerlike. “By the clump of trees?” I ask.

There’s an uncomfortable pause.

“No,” she says. “Those are our horses.”

We keep walking. Brenner asks, cautiously, “Your rifle’s unloaded, right?”

I open the bolt. “Right.”

We head up a little rise and spot more deer. Six muleys, three bucks of legal size. Ever so slowly, I ease the rifle bolt forward and raise the scope to eye level. Brenner, looking at the deer through her binoculars, whispers the go-ahead. They’re legal. Through the crosshairs, I can see a clear shot. I can also see my point of decision: To take a life or let it go.

I’ve been walking with a deadly explosive. Now I’m aiming it.

We live in a world too cleanly divided. We are red states or blue states, urban or rural, creamy or crunchy. The outdoor world suffers miserably from this binary split. We are hikers or hunters, two cultures divided by a chasm of ignorance and mistrust. We wear Patagonia R2 fleece or Mossy Oak Break-Up camouflage. Our seasons have different names: One person’s duck season is another’s ski season. The catalogs in our mailbox define us: Cabela’s or REI. Six years ago, the rift was distilled in two political bumper stickers. Sportsmen for Bush. Climbers for Kerry.

I’m troubled by this great divide. As a member of REI Nation, I’ve been a backpacker, a car camper, and a bird-watcher. I’ve thrown bait and flies at Alaskan salmon and Rocky Mountain trout. I’ve climbed Cascade volcanoes, paddled Sierra rivers, and I’m a skier of catholic taste. But I’ve never been hunting.

I find that a little strange. Hunting is, after all, the original outdoor activity. But what’s more puzzling is the fact that nobody’s ever asked me to go hunting—or wanted to know if I’ve ever been. I’m so deeply smothered by the fleecy bosom of my demographic that the notion never arises. In this polarized world of us and them, hunting is something they do.

And who are they? If you believe Hollywood type casting, they’re beer-guzzling good old boys. They’re Toby Keith in a trucker cap. They love wildlife they can kill, but don’t have much use for the rest of nature. They run generators in campgrounds and drive F-250s with NRA stickers in the window. Not our kind, dear.

At least that’s the way I used to think. And then, little by little, my assumptions changed. As an outdoor writer, my job often requires me to drop into backcountry terrain where I’m a stranger to the land. Years ago, I discovered that sportsmen offer an excellent perspective on the local wild. I’ll find the best hunter in the county and spend an afternoon with him, without weapons, crashing through the forest. A hunter’s eyes, ears, and nose are tuned differently than a hiker’s. He sees things that are invisible to those of us trained to follow signs and stay on trails.

I’ve also learned that there are plenty of hunters who are hikers, and vice versa—among them, readers of this magazine. For them—and maybe that includes you—the notion of a divide would be a mystery, perhaps even an insult.

Still, every statistic indicates that crossovers are a distinct minority. Among most backpackers, and among most hunters, the culture divide grows wider. In a hiking club, the word “hunting” can suck all the air out of the room. It’s become a conversational taboo.

Any issue that volatile is worth investigating. So I decided to meet the hunters, explore their world, and attempt the pursuit myself. I wanted to bridge the gap with a gun.

I figured I’d need a partner, so I called my friend Mike “Gator” Gauthier, who was then the head climbing ranger at Mt. Rainier National Park. (He’s since been promoted to Interior Department headquarters in Washington, D.C.) I explained the project.

“So…we’d actually go hunting,” he said. “Not just hang out and watch some hunters?”

Yes.

“I’m in,” he said. “How do we do it?”

“I have no idea,” I told him. “Maybe we should find a hunter we can go with.” That’s when we realized that, well, we didn’t know any hunters.

Hikers or not, our lack of gun-toting acquaintances wasn’t surprising. Hunting in America is a dying pastime.

In my home state of Washington, nearly one in three hunters has hung up his rifle in the past decade. It’s happening everywhere. Hunting permits are down 20 percent in West Virginia over the past 10 years. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the number of Americans who hunt has fallen 25 percent since 1980, to less than 13 million.

Hunting’s decline isn’t due to lack of game. Whitetail deer are overpopulated in 73 percent of their range. A century ago, only 50,000 elk roamed the continent. Today, the combined North American herds total one million strong.

The biggest culprit is land development. Specifically, the loss of private farmland, where much of the country’s hunting has traditionally occurred. According to the National Farmland Trust, two acres of prime American farmland are lost every minute. If hunting were hiking, that would be like losing one Grand Canyon National Park each year.

Hunting’s decline can’t all be blamed on the loss of open space, though. Powerful cultural forces have also been at work. Hunting is commonly passed down from fathers to sons and daughters. But over the past two generations, the hunting gene has withered on the vine.

I saw it happen in my own family. My grandfather was a duck hunter. When my father was young, Grandpa Barcott took him out for predawn shotgunning parties. “We went out with dad’s buddies, and they had a great time—cooking up steaks, hash browns, the whole deal,” Dad told me. “But by the time I got good enough with the shotgun to shoot ’em on the fly, in my early 20s, I found that I just didn’t want to do it.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“The ducks,” Dad said. “They were just too beautiful.”

Sooner or later, every hunter comes face to face with the same issue. To hunt is to kill a living creature. And we’re not talking about squashing a mosquito. In the early stages of my hunting interest, I browsed the rifle section of a Dick’s Sporting Goods store. My six-year-old son was with me. “Why do you want a gun, Dad?” he asked.

“I’m thinking about maybe going deer hunting,” I said.

He thought about that for a minute.

“Why do you want to shoot a deer?” he asked.

My answer was so half-hearted and halting that a passerby overhearing the conversation would have been embarrassed for me. Clearly, I had some philosophical work to do.

I went to the experts for perspective.

I put the question to Bruce Friedrich, vice president of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), and Ted Nugent, guitar hero and prolific hunter: Should we hunt?

Friedrich treated the phrase “ethical hunting” as an oxymoron. “There’s no ethical difference between shooting a deer and shooting a cat or a dog,” he told me.

“The deer has the same intelligence and range of emotions, the same capacity to feel pain.”

But don’t hunters help keep the deer population in check?

“Some people just enjoy shooting defenseless animals, and that’s one way they justify it,” he said. “Future generations will look back on our shooting animals with the sort of moral incredulity that we reserve for past abuses of human beings.”

When did hunting cease to be morally justified?

He thought for a second. “It could have been phased out 10,000 years ago, with the development of agriculture.”

Ted Nugent begged to differ. “Don’t let the lunatic fringe keep you from hunting,” he said. (Actually he emailed me between hunts. The Nuge is a very busy beast slayer.)

Nugent, of course, is the 1970s rock star who reinvented himself as America’s foremost hunter. Nugent views animal rights advocates like Bruce Friedrich as nutjobs divorced from the natural cycle of life.

“Do we really need to shoot wild animals when there’s a Safeway down the street?” I asked The Nuge. “Is this just murder as sport?”

“That’s like saying recorded music is available, so none of us needs to make our own,” he said. “Vegetables are on store shelves, so we don’t need to tend gardens. I’m sure we could find someone else to breed our wives for us, too. Not me. I have nothing to do with the mass assembly of food. I hunt, kill, butcher, and cook my own, knowing that it’s the healthiest, most natural nutrition available to mankind—while at the same time bringing balance to the environment. Remaining connected to the good Mother Earth is a driving force in all the hunters, fishermen, and trappers that I know.”

“Hunting,” Nugent assured me, “will cleanse your soul.”

As much as my soul could use a scrub, I didn’t put a lot of faith in the Motor City Madman’s method. I doubted that any epiphanies would come attached to a smoking gun. At the same time, I found myself falling closer to Nugent than to the guy from PETA. I’m an enthusiastic carnivore. Over the past 40 years, dozens of cows, pigs, and chickens have been slaughtered on my behalf—butchered out of sight and out of mind. Like a lot of Americans these days, I’m trying to live closer to my food. I’m eating backyard vegetables and buying eggs from my neighbors. I decided it was time I met my meat.

Ironically, explaining my desire to kill a deer to a six-year-old was the most challenging aspect of preparing for a hunt. Everything else fell into place in short order. In August, Gator found us a hunter. “Her name’s Jennifer Brenner,” he told me. “She’s the girlfriend of my friend Shaun Bristol. They’re both state park rangers over in eastern Washington.”

And acquiring a weapon was surprisingly easy. I strolled into a local gun shop, picked out a used bolt-action Ruger, and laid down my Visa card. The sale was delayed for 10 minutes while the salesman carried out a background check to make sure I wasn’t certifiably insane, or an ex-con, or both.

The real problem was where to store it. “Go hunting, by all means,” said the wife. “Just don’t bring the gun anywhere near the house. Ever.”

Gator offered a solution. He had secure storage and no kids. I became a rifle divorcee. Gator got custody. I got visitation rights.

I called Jennifer to discuss what we’d hunt. Hunting elk seemed an overreach for a rookie. I hadn’t earned an elk hunt. Moreover, I’d moved among elk in the mountains. They are majestic creatures. I doubted I could pull the trigger on one. Deer, on the other hand, are common as squirrels. They’re tick spreaders, garden killers, poop-pellet producers. Therefore, deer.

“Have you handled a rifle before?” she asked.

Nope.

She told me to take a hunter-safety course. “If you’re going hunting with me, we’re going to do it the right way.”

If you’ve ever suffered through the mind-screwing tedium of childbirth classes, you have a fair idea of the hunter-safety course. It’s childbirth class with bullets.

On a Monday evening in September, I slipped in the back door of the Bainbridge Island Sportsmen’s Club and claimed one of the few empty seats. The Sportsmen’s Club was straight out of “The Red Green Show”: knotty pine paneling, a moose head above the fireplace, and a sign that read “Absolutely No Drinking While Shooting Is In Progress.”

If hunting is in decline, you wouldn’t have guessed it by the turnout. The place was packed.

“Welcome to Hunter Safety,” said Jim Walkowski. A grandfatherly man in an orange vest and green ballcap, Walkowski is an ex-cop and Navy survival instructor who’d taught this class for 35 years. “Hunting is a privilege,” he told us, “and safety is our number one priority.”

Safety, it turns out, is a relative thing. Walkowski assured us that hunting was safer than playing football or driving a car. “Of the 25 most popular activities in the United States,” he told us, “hunting is the 13th safest.”

I looked it up. According to the International Hunter Education Association, a group that promotes hunter-safety courses in the U.S. and Canada, there were 241 fatal hunting accidents from 2005 through 2009. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that about 12.5 million Americans hunt every year. That works out to a risk rate of about 0.38 fatalities per 100,000 hunters annually. Comparing the risk rates of different sports is a tricky and often suspect proposition—there are a lot of apples-to-oranges problems—but based purely on fatalities per participant, hunting appears safer than, say, swimming (6.57 drownings per 100,000 swimmers) and bicycling (1.87 fatalities per 100,000 cyclists), but not, technically, football (0.2 per 100,000).

And yet over the five-day course, Walkowski and his fellow instructors rattled off an endless string of hunting-accident anecdotes. One guy’s friend got shot climbing over a fence. A husband and wife picked up their rifles after lunch. “Boom!” said Walkowski. “Killed their partners.” One evening, Walkowski pointed to his rifle and said, “That .30-30 right there, my brother-in-law killed his brother with it. Drinking. So there you go.”

Holy crap! There you go what?

I stepped outside and rethought the whole proposition. It occurred to me that there might be a scared-straight method to Walkowski’s madness. “Maybe it’s like reading Accidents in North American Mountaineering to climbing students,” I told my wife. “Gets them to pay attention.”

Night after night, I returned to the Sportsmen’s Club to receive hot cups of Walkowski’s wisdom. In fairness, I learned quite a lot. Stuff like: Aim for a deer’s lungs, not its head. It’s illegal in Washington to have a loaded rifle in a vehicle. If you get some dirt in the muzzle, a fired shot could split the barrel like a banana peel.

Walkowski and his fellow Club members were friendly, generous men. One of them, a former Army sniper, gave up an afternoon to let me shoot his rifles on the range. (I practiced with my own as well.) And yet, as I slipped my Subaru between massive pickups in the parking lot, I couldn’t help but feel like a blue spy in the house of red.

That’s worth considering. One of the sources of the hiker-hunter rift can be found in the post-Vietnam shift in military culture. Prior to the 1970s, military service was an experience common to the American man. (A draft will do that.) Basic training acquainted a wide spectrum of society—conservative and liberal, rich and poor—with firearms. Nowadays, that doesn’t happen. Today’s soldiers and sailors are self-selected, and they tend to be a politically conservative demographic. Distrust of the military, driven by misadventures like Vietnam and Iraq, and years of urban violence and mass murders like Columbine and Virginia Tech have made a hostility toward guns part of the liberal package deal. Almost all of my liberal friends consider themselves environmentalists. Almost none own a gun. If you’re not comfortable around firearms, you aren’t likely to become a hunter.

The irony, of course, is that hunters founded the modern conservation movement. Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot, Aldo Leopold, and Stewart Udall all hunted. (Though John Muir and Rachel Carson did not.) In the 1930s, conservation-minded hunters crafted the Pittman-Robertson Act, which established some of the nation’s first habitat-restoration programs using gun and ammunition excise taxes. Last year, $300 million in gun and ammo tax went to conservation programs—and that’s to say nothing of the more than $1 billion collected in hunting and fishing permit fees.

The big rift opened in the late 1970s. Conservative leaders realized they could use gun control as a wedge issue to turn rural, conservation-minded voters against urban enviros. Many liberal leaders categorically embraced the era’s animal rights movement, which painted hunters as cold-blooded murderers.

The hard feelings still linger. A couple of years ago, I praised a local wilderness group for reaching out to hunting and fishing groups. The director of the group thanked me for the kudos, but admitted that the great reach-out wasn’t a huge success. “We lost members over that one,” she said.

Opening day broke cold and clear. On the first Saturday in October, I rose in the predawn darkness and pulled on two shirts, a thick hoodie, a down vest, a fleece jacket, a Gore-Tex shell, and a bright orange vest. With all of that padding, I felt I could stop a bullet myself. But I needed it. Outside, it was 31°F, a light dusting of frost on the ground. In the rolling hills above the Snake River, hundreds of hunters fueled up on coffee.

Plan your hunt, hunt your plan. Those were Jim Walkowski’s words. Our plan was to hunt three types of terrain over three days: wheat fields, river bluffs, and mountain forest.

Unfortunately, Gator was delayed. “Duty calls,” he told us from his office at Mt. Rainier. “We’re opening a new visitor center, and the Interior Secretary is here.” Gator would arrive late on the first night.

As a streak of blue snaked into the black sky, Jennifer and I set out across an open field. We were hunting her family’s 700-acre farm about a mile from the Snake River, prime deer habitat. “The mule deer and whitetail come into the fields to feed on grain left over after the harvest,” she told me.

The family farm was also a practical choice, as we wouldn’t have to worry about access or opening-day crowds. For backpackers, route planning is as easy as opening a Trails Illustrated map. For hunters, though, land access is a challenge. Not all public land is open to hunting. Rules change even within states. Shooting a whitetail deer might be legal on one side of a dirt road and illegal on the other.

As it became light, Jennifer began pointing out signs of wildlife. A badger hole, a coyote print. “Deer track,” she said, pointing out a print I’d nearly stepped on. “It’s a buck.”

“How can you tell?”

“Bucks have dewclaws that leave a little mark in the ground; does’ dewclaws don’t make prints.”

We kept walking, careful to keep our profiles below the ridgeline. Jennifer kept her body still. Her eyes constantly scanned the horizon. She learned how to spot wildlife when she was a kid, going hunting with her dad.

At the top of a rise, we stopped to glass the distant fields.

“There’s one,” Jennifer said. “A whitetail.”

It took me a while to find the deer. It was a tiny speck on the landscape, at least a mile distant.

We crossed a barbed-wire fence and hopped a stream. As a hiker, I would have overlooked this as dross land, the junk you’d cross to reach the trailhead. As a hunter, it came alive with excitement and potential. My eyes became attuned to the terrain. Pockets of brush—chokecherries and rosehips, mostly—turned into deer refuges. Cresting a hill became a test of stealth and readiness. Ever so slowly, I began to think like a deer. What’s good cover? Where’s the food?

As we came over another rise, Jennifer and I froze. Four whitetail deer grazed in a pocket of brush below us. In an instant, they spotted us and bolted. They were over the hill before I could even swing the rifle off of my back.

My hopes crashed. I knew the deer would move. I just didn’t know they’d move so fast.

“Why don’t you put one in the chamber,” Jennifer said. “We’ll be ready next time.”

I loaded a bullet and we kept walking, a little quieter now. All we could hear was the sound of wheat stalks crunching under our boots. Then I spotted them. One deer. No, two.

Then I saw all six, browsing in a wheat pocket below us.

I glanced at Jennifer. She and I slowly backed away from the edge of the bluff, erasing our bodies from the herd’s sight. We crouched and glassed them. “Muleys,” Jennifer whispered.

Mule deer are less skittish than whitetail deer. A whitetail will be in the next county by the time a muley starts thinking about trotting away.

At least one of the deer looked legal: Three points on each side of his rack. I belly-crawled to the lip of the bluff. Grass tickled my cheek. The buck stood broadside, offering a perfect target. The others were bedded down. I glanced at Jennifer.

“The one standing,” I whispered. “Is he legal?”

“Yes.”

I looked through the scope and confirmed it.

And here we came to the point of decision. “You can’t call a bullet back” is a common saying among hunters. At this moment, I can take my finger off the trigger and walk away. But I don’t. Neither my head nor my heart feels the flutter of any last-second moral qualms. Instead, I find myself thinking about bringing food home to my family. Ridiculous? Maybe. But that’s what’s in my head when I pull the trigger.

BOOM.

Though I’d fired it a couple of dozen times, the .270 still rattles me to the core. The calm, clear-eyed world seen through the riflescope goes herky-jerky. For a full second, all six deer freeze.

“Is he hit?” I ask.

“Yep,” says Jennifer. “You got him.”

Five of the deer scatter. They hop over the bluff and tear east for the Snake River. The sixth deer doesn’t get that far. He takes one full step, then bucks high into the air and collapses on his side. He kicks once more before lying still. He’s dead.

“Wow,” I say. “My god.”

Jennifer and I stand and watch the herd disappear over the ridge.

“So how did it feel?” she asks.

“Amazing,” I say, and can’t find words after that. Here’s what I feel, and it’s not going to make me popular among my vegetarian friends. I feel happy. Proud. Fulfilled. The two minutes and 10 seconds that elapsed between the time we spotted the deer and when I pulled the trigger (I kept my tape recorder running, and timed it later) were among the most intense, primal, and profound moments I’ve ever spent in the outdoors. I can’t explain those feelings. But I can’t deny them, either.

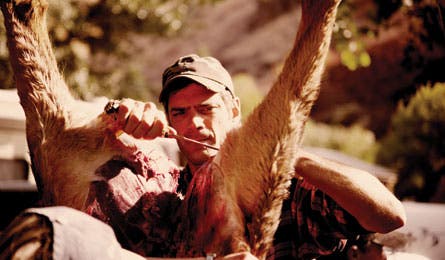

“Field dressing” is a pretty term for a bloody, messy, disgusting operation. It involves cutting open a freshly killed animal and removing its guts and organs. It’s done on the spot, at the point of the kill—otherwise, the carcass is too heavy to haul. The guts are left for coyotes and other scavengers. Jennifer tutors me on the finer points.

“Start your cut here,” she says, pointing to the deer’s nether regions. Jennifer and I spend the next half an hour slicing through deer hide and peeling through the animal’s thin, mucousy layer of fat. The shifting breeze sends a briny funk of odor—the smell of warm blood mixed with body gasses—up my nose. I fight back a dry-heave.

By the time Gator arrives that evening, my deer is cooling in a local meat locker. “Time to get you yours,” I tell him. I can’t believe I’m saying those words even as they leave my mouth.

Gator is a bit of a legend in mountaineering circles. He pulled injured climbers off of Mt. Rainier for nearly 20 years. He’s almost as famous for his eclectic collection of friends. Senators, CEOs, Everest-climbing superstars, and backwoods hippies all consider Gator their righteous bro. One of those friends, Ted Cox, is a seasonal Rainier employee in his 60s who’s come along on the hunting trip to…well, nobody’s quite sure why he’s come along. Ted opposes hunting like dogs oppose cats—with loudness and constancy. “I’m here to witness the slaughter,” Ted declares.

The next morning, Gator, Ted, and I are up just before dawn, pounding coffee. Gator’s day often starts with a 2 a.m. alpine start, so this is a lazy Sunday for him. “Sure beats getting up in the middle of the night in a storm on the side of a mountain,” he says.

“I can’t believe you’re really going through with this,” scolds Ted. “What have you got against some poor, defenseless creature?”

Gator laughs. “Aw, Ted. What about those fish you like to catch?”

“That’s different,” says Ted.

We hike through fields to the sloping coulees of the Snake River canyon. At the rim we pause to take in the scene, a classic Western vista that hasn’t changed much since Lewis and Clark came upon it more than 200 years ago. The Snake drains most of Idaho, and the river’s breaks are formidable—dry gulches and ravines falling away and folding in on themselves for more than a mile before hitting water. Deer, coyotes, and other wildlife come here to hide out in the rock crevices and pockets of brush.

Gator and I scramble over steep terrain. Because of the rifle on my back, I find myself placing steps with newfound precision. A tumble here could easily lead to a misfire, or worse.

“You’ve got to add something to the equation when you’re hunting the breaks,” Jennifer had told us. “That’s whether you can haul a 150-pound deer up the cliffs after you shoot it.”

“Honestly, I’m not that worried about bagging a deer,” Gator says. “The main thing I’m concerned about is not making a lousy shot and letting some poor animal wander off wounded.”

We crouch by a pocket of trees and brambles. “There’s got to be something in there,” I say. “Why don’t you set up a shot while I flush?” Gator hugs the ground and props himself on his elbows. I toss some rocks into the trees. After the crackle and thunk, movement.

“Two of ’em,” I say.

“I see them,” Gator murmurs.

A doe and her yearling emerge from the shadows. Gator takes his finger off the trigger. Our tags are for bucks, not does. We watch them disappear over the next ridge.

That night we return empty-handed. Ted is visibly pleased.

“Nothing killed today, fellas?” he says. “What a shame.”

Centuries ago, kings employed jesters to keep things lively and to deliver hard truths in a nonthreatening package. For Gator and me, Ted plays the jester for our collective conscience. He gives voice to the inner hiker in both of us. All around us, sportsmen speak of “harvesting” deer, as if living creatures are barley. Ted reminds us that we are, in fact, killing animals.

Day three: Gator’s last chance at a deer. We decide to hit it hard, hunting the Blue Mountains’ ponderosa pine forests in the morning and working the isolated Grande Ronde River breaks in the afternoon.

At first light, Gator and I and Shaun Bristol, who has joined us for the morning, set up on the edge of a Blue Mountain meadow. We’d seen some does browsing in the field at dusk the previous night, and figure we might catch a buck among them this morning. We lean against the rough bark of the ponderosas, trying to blend in and remain motionless. If open-field hunting is all about covering ground and flushing game, forest hunting requires opposite tactics: Hide and wait for the prey to come to you. Or so we think. We’re hunting for the first time without Jennifer—a solo flight of sorts.

As Gator creeps forward for a better view, a spear of meadow barley nails him in the eye.

“God damn,” he says, pulling the barbs out of his eyelid.

“Um, guys…” Shaun is trying to get our attention.

“Did you get it out?” I ask. Gator shakes his head.

“Guys…” Shaun says. I look back at him. He points to two whitetail bucks quietly crossing

the road 20 yards behind us.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” I say. The deer catch our movement and bolt into the

forest. I laugh at the thought of Gator and me standing there, Jethro and Elmer Fudd, as our prey fearlessly strolls by.

In the afternoon, we load our packs with food and water and hitch a ride to the rim of the Grande Ronde River canyon. The Grande Ronde, a tributary of the Snake, unwinds like a curling ribbon through the Columbia Plateau near the Oregon-Washington border. It’s world famous for its steelhead, and the dry, brushy ravines above the river are prime habitat for deer, coyote, wild turkey, chukar, black bear, elk, and bighorn sheep.

We have a plan. Gator and I will start about a quarter-mile apart at the top of the rim, then pick our way down in a V that meets at the bottom of the ravine. I’ll flush the deer in Gator’s direction.

As I heel plunge down the scab-land ravine, my eyes scanning for movement, Gator in my periphery, a sort of perfect moment comes over me. My own hunt is done. Because I’ve already bagged my deer, I can relax and enjoy the hike, the camaraderie, the strategy and cunning, the suspense, and the pure joy of physical movement in the wild. Gator, on the other hand, hunts with all the pressure and anxiety of a live trigger. If you’re doing it right, hunting comes with a huge responsibility. You’ve got to line up a good shot, not carelessly wound the animal, not shoot something illegal, not crack off an errant bullet that flies into a house a half-mile away, and not kill your partner. It’s not that far from mountain climbing, in fact. A certain amount of danger and risk enhances the experience of moving across wild terrain. It revs up your adrenaline and puts the senses on edge. Hunting combines strategy, motion, experience, skill, and danger.

It does something else, too. By the end of our three-day hunt, I feel like I’ve been given a fresh pair of eyes. Landscapes that were once barren to me become lush and vibrant, alive with life, crackling with possibility. Where once I saw lowland scrub—white noise for a backpacker—now I see a living habitat where rosehip bushes function as secret deer beds. Blank hillsides aren’t blank at all; they’re terraced with game trails. I see water and imagine the animals it might draw. I start to think like a predator. To be perfectly frank, hiking as a hunter is fun.

After a couple of hours, I’ve flushed only a doe and a mangy coyote from the brush. Gator and I take a break. The late-afternoon sun beats down, and we strip off layers.

“I don’t know if it’s in the cards for us today,” I say. That’s when Gator spots the buck.

It’s just below us, in a dry creekbed: Mule deer, a buck of unknown antler points. The deer takes off uphill, moving over a ridge before Gator can get a look through the scope.

Gator scrambles across the creekbed and muscles up the ravine. I follow for a while, but I’m in no shape to be chasing uphill after a man who has climbed Rainier 190 times.

The buck keeps moving high. Gator follows. Over one ridge, then another. I shadow them from below. Finally, Gator peeks over the edge of the last ridge and puts the buck in his crosshairs. The deer stares back at him.

“He was at an angle where his antlers lined up exactly in a row,” Gator later tells me.

“So I couldn’t get a read on his points. I couldn’t confirm that he was legal.” They stood there like that, frozen for a few moments. Then the deer turned. Gator saw the antlers—a three-pointer, legal—but the deer’s butt was angled toward him. A lousy gut shot if he took it. A wounded deer, the meat spoiled. Plenty of hunters have pulled the trigger in that situation.

Gator didn’t.

As the sun fades behind the canyon’s rim, we hike out through an old apple orchard to a road beside the river. There, Jennifer, Shaun, and Ted—a happy, relieved Ted—greet us with a warm truck and cold beer.

“Well, what do you think of hunting now?” Jennifer asks me.

“Harder than it looks,” I say. “But a hell of a lot of fun.”

“Are you going to become a hunter now, Bruce?” Ted asks.

It will take some time, some reflection, before I can answer that question with any certainty. To do it right, hunting requires long-term preparation. The payoffs, though, can’t be expressed in antlers or meat. Hunting offered this lifelong hiker an enriching and profound new way to interact with the land. Different landscapes opened up to me. I’ve met the Cabela’s crowd on their turf and, hopefully, shattered some of their own stereotypes about fleece-wearing treehuggers.

So call me a hunter. I’ve got visitation rights with my rifle, and if someone asks me to join his deer camp next season, I just might grab it and go.

Bruce Barcott brought home 55 pounds of venison from this hunt. He wrote about mapping his new home, Washington’s Bainbridge Island, for the May 2010 issue.