I Will Survive

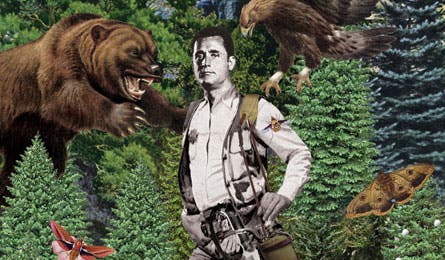

'Illustration by Nicola Ackland-Snow'

Illustration by Nicola Ackland-Snow

Bear Grylls (courtesy).

Les Stroud (courtesy).

Bear Grylls (courtesy).

Les Stroud (courtesy).

John Rambo (courtesy).

Bear Grylls (courtesy).

Mangy beasts with an insatiable taste for man-flesh lumber toward me, and while I have tried to prepare for everything, I am not ready for this: grunting, huffing rogue bears crashing through thick woods, 200 feet due east, picking up speed, closing fast. I can’t see them, because it’s late in the day, and cloudy. And I can’t hear them, because their ravenous rumbling is drowned out by the rushing of a raging river, along whose eastern banks I collapsed, sweating and gasping, just 15 minutes ago. To the south stretches a nearly impenetrable maze of canyons and thick forest; to the west, the angry river, frigid and deadly. Eight long, steep miles to the north, the trailhead; and 60 miles miles beyond that, Portland, Oregon. Actually, I’m not certain that the impenetrable forest and canyons don’t lie to the north, and that I didn’t hike in from the south, which would mean the bears would be lumbering from my west, and the river would be roaring due east. I have never possessed a very good sense of direction.

“This is bad,” I mutter, as I hunker next to a pine tree (or spruce; I can’t tell the difference), squinting into the darkening woods, wondering if it would be more painful to be eaten alive, or to freeze to death in the icy water to my west. Or east.

“This is very bad,” I say. I’m virtually alone, with virtually nothing other than my clothes and a knife and a piece of flint fastened to a piece of elk horn my older brother gave me before the trip. “I bought it at a hippie survival shop 20 years ago,” he said. “They told me it worked.”

“I’m doomed,” I whimper into the dark. I hope the bears don’t hear me. “I’m hopelessly doomed.”

A few months earlier, I was sitting around watching a guy bite the head off a wriggling trout while I shoveled mu shu chicken into my mouth and debated whether later that night I would surf the internet for new information on old girlfriends or work over a pint of Chunky Monkey (or both!) when I had one of the more stupid ideas of my stupid-idea-infested life. I decided it would be fun to watch a year’s worth of Man vs. Wild (the television show starring the fishhead-biter) and Survivorman (starring a shorter, chunkier, balder, more dolorous guy who is Canadian) in the course of a couple of weeks. Also, First Blood, starring Sylvester Stallone as Johnny Rambo, who lives mostly in caves. Then, armed with whatever knowledge about fish-eating and shelter-building and general survival I had gleaned, I would enter the wilderness myself, armed with only a knife and a piece of duct tape, or whatever those guys took when they entered the wilderness.

Then I actually watched another episode of Man vs. Wild and one of Survivorman. “I’m hopelessly doomed,” I thought. “I’m so hopelessly doomed.”

Dusk has turned to darkness, the bears are moving, and the temperature has dropped. Somehow, I have managed to build a fire. Emergency matches helped.

Peering into the flames, I say, “It looks beautiful here, but looks can be deceiving,” which is what Bear Grylls, the star of Man vs. Wild, said in the Sierra once. Then I say, “There’s a fine line between a land of paradise and a land of nightmares,” which Les Stroud, the star of Survivorman, said another time, in Costa Rica. Talking like Les and Bear makes me feel better. Actually, talking in general makes me feel better. This is why, when I first became aware of the rogue bears, instead of taking evasive action, or making loud noises to scare them away, I said, “Those are creatures that have developed an insatiable appetite for man-flesh.” Saying words like “insatiable” and “man-flesh” has always cheered me. “Infested,” too. I don’t know why. Saying “rogue” makes me happy, whether “rogue bear” or “rogue wave” or “rogue elephant.” When I was young and terrified–which for me covers ages zero to 18–while other boys were learning knots and perfecting the art of rubbing sticks together to make fire, I was memorizing words like “arch-fiend” and “juggernaut,” thrilling myself with the delicious feel of “puny earthlings” and “hopelessly doomed.” Now, in the peril-infested, unforgiving wild, I see the terrible error of my ways. I should have memorized less, taken shop class more. No matter how much I say, “I’m hopelessly doomed,” nothing changes. I haven’t eaten in six hours. (That’s a long time for me; I tend to snack.) I have no drinkable water. And no place to sleep. I’m virtually alone, in a deep, forested river gorge. Night falls. The man-flesh-eating creatures circle. I’m hopelessly doomed. But really.

From First Blood I learned that if you are a special forces military guy like Johnny Rambo, you know how to make booby traps with sharpened spikes to kill hunting dogs that are on your tail, and that even though you revere all creatures and mourn their passing into the great spirit world, sometimes you must accept killing as the cost of life. Johnny Rambo carries a foot-long knife, and lugs around a giant shank of what appears to be moose meat. It looks tasty. He is, according to his former commanding officer, “a man trained to ignore pain, to ignore weather, to eat things that would make a billy goat puke.” Johnny Rambo doesn’t talk much and when he does, he says only unbelievably manly things, like, “Don’t push it or I’ll give you a warning you won’t believe.” I, on the other hand, tend to say things like “On the other hand…” and “I can empathize, but…”

After watching First Blood, I spend a lot of time telling people about the trip. “Just me and a knife,” I say, “and whatever food I can kill.” I love saying that. I love it like I used to love saying, “But what about the gaping jaws of the mighty crocodile?” whenever my camp counselor in northern Wisconsin suggested I stop reading the Man Thing comic book and get in the lake for swimming lessons. I love saying “me and my knife” so much and say it so often that I have no time to watch the television shows from which I’m supposed to learn survival skills.

Finally, eight hours before departure, I sit down to watch 12 hours of television. (I fast-forward through the boring-looking spots). I learn that Bear Grylls, in addition to having trained as a British special forces soldier, brings with him a team of camera operators that films each “death-defying” encounter he has with the wilderness, which means they really aren’t so death-defying at all. Also, that he receives the advice of various local experts regarding tasks like constructing rafts from jungle plants and making tents from deer hides. Still, he is the youngest Englishman ever to scale Everest, and he does jump out of small airplanes. I also learn that Les Stroud lugs his own camera equipment through the unforgiving wilderness and does everything himself, with no camera crew or local experts to help.

Basically, I learn that I’m hopelessly doomed.

“Up here, there’s a saying,” I murmur to the creeping darkness, and to the lurking bears that are due east. Or west. “Stop thinking and you’ll stop trying. Stop trying and you’ll die.” It’s what Les said once in the mountains.

I have been quoting from the shows for the past few hours. I haven’t quite mastered Bear’s or Les’s means of extracting nourishment and protective cover from the wild, but I hope that by speaking like them, I might start thinking like them, which will lead to me actually acting like them. “Most fear is born of ignorance,” I say (Les, Sonoran Desert), as the bears lumber closer. Then, “Raw grasshoppers can carry tapeworms.” (Les again, same desert.)

I have grown from a boy who squeaked, “Puny earthlings!” in times of stress to a man who quotes television shows while bears with an appetite for man-flesh circle. Why can’t I be more like the quiet, strong men I know who spend weekends installing drywall and ripping up floorboards? They aren’t Rambo, but at least they do things with their hands and keep their mouths, for the most part, manfully shut. I first successfully operated a French press coffee machine a few months ago. I’m 52 years old. Why haven’t I ever installed drywall? Why am I so gabby? Why hadn’t I talked less about me and my knife in the past couple of weeks and spent more time studying the TV shows?

I’m so tired, and cold, and–I must admit, because I have learned the consequences of dishonesty from witnessing the sad and ugly fate of the corrupt cop who tried to corner Johnny Rambo–frightened.

“It’s really hard to get motivated with nothing in your system,” I whisper. Les whispered it in the Arctic. “A little bit of meat in my belly tonight would go a long way to making me warmer.” He said that in Canada’s boreal forest.

“We just had dinner, and you can stay in the tent if you’re scared,” says an eerie, disembodied voice from the blackness. It belongs to my 16-year-old nephew, Eddie, who I hired at the last minute to accompany me on my trip, as support staff and emergency help in case anything went drastically wrong. Eddie is the “virtually” in my “virtually alone.”

Eddie has climbed Mt. Hood, Mt. St. Helens, and Mexico’s 17,158-foot Iztaccihuatl. A week after our trip, he will be heading into Canada’s Purcell Range, where, the permission slip from his school warns, he might encounter grizzly bears, lightning storms and deep, deadly ice crevasses. Eddie is an excellent student, a kung fu enthusiast, and a javelin-throwing champion. He is strapping, kind, preternaturally cheerful, and strong. Inviting Eddie had seemed, survival-wise, like a no-brainer.

“I only had dinner because I felt weak from hunger and because we failed to catch any food,” I tell my young aide-de-camp. “And on a related note, how did I ask you to address me while you’re on the clock?”

“We didn’t catch any food because you wouldn’t let me build a death pit,” he says, then pauses. “Sahib.”

“I hate the thought of killing anything,” I say. “It’s the last thing I’d advise.” (Les said that in Costa Rica.) “Besides, where’d you learn about death pits? Bear and Les never built death pits.”

Eddie pulls a book from his pack called How to Survive in the Woods. It’s where he read about death pits. Eddie’s mother bought the book and gave it to him when she heard he was going camping with Uncle Steve. I have tried to explain to her and other relatives that when I got lost in the Missouri parking lot, it was because I was weak from heatstroke, and that the time I thought a pack of marmots was stalking me deep in Colorado’s Weminuche Wilderness, they really were stalking me. But she didn’t want to take any chances.

“It’s not the snakes or scorpions that scare me, but running into a pack of wild peccaries,” I tell my nephew. “They’ll attack you in groups.” (Les said the same thing in the desert.)

“What’s a peccary?” Eddie asks.

“Excuse me?”

“I mean, what’s a peccary, sahib?”

“They look like little wild boars, but they are vicious and nasty and dangerous.”

“That’s cool.”

“If you think that’s cool,” I say, “check this out. According to Les, they can’t look up. So you just stand on some rocks, and they can’t see you. And you can pick ’em off, one by one.”

“Can we build a death pit tomorrow, sahib?” Eddie asks. “You can make them with or without the sharp killing spikes on the bottom. But we have to put it on a game trail.”

I tell Eddie I’ll think about it.

Day two, virtually alone, I wake chilly, hungry, and tired. I can feel my body feeding on itself, cannibalizing its own nutrients. I need to orient myself. I must construct a wilderness compass.

“What about looking where the sun’s rising, sahib?” Eddie says. “That’s east.”

“Number one, as support staff, you’re supposed to follow my directives, not make strategic suggestions,” I say. “And number two, what if the sun were directly overhead, and what if we were in the Scottish Highlands, like Bear was in that episode when he got sucked into the bog pit, or in the Arctic, where the sun hardly ever moves, surrounded by polar bears, like Les was that time he had to get by on just a few bites of raw seal meat a day? What if you were being hunted by a corrupt, hopelessly doomed cop who couldn’t understand your psychic pain and all you’d been through in ‘Nam, and you spent most of your time killing dogs and eating moose and hanging out in caves, like Johnny Rambo did? Then what would you do? Huh? Then what would you do?”

“I dunno,” Eddie says.

“I dunno, what?”

“I dunno, sahib.”

“It may look beautiful,” I mutter darkly, “but this is a place where even the most experienced mountain-goer can get into trouble.” (Bear, in the Sierra.)

I jab a stick into the ground, and mark the end of its shadow with a rock. In 20 minutes, I will take another reading, mark the end of the stick shadow again with another rock. Then I will trace a line between the two rocks, which should give me an east-west reading. In the meantime, because I have temporarily ruled against the death pit, and because I don’t want stomach cramps to interfere with my day’s planned survival activities, which involve hunting for food, building a shelter, and starting a fire without matches, I tell Eddie that now might be an opportune time to break out a little bit of granola. Also, that he should hunt for some pine needles while I assess our situation.

“A cup of pine-needle tea offers five times the amount of vitamin C as a lemon,” I say. Bear said it, too, in the Sierra.

Half an hour later, we are sipping delightful, tangy pine-needle tea. Or maybe it’s spruce. (Which, I know from Bear, contains eight times the vitamin C as a glass of orange juice.) Whatever the specific needle, it’s good.

The wilderness compass is another matter. After breakfast, I discover that I have placed my entire stick and stones setup in the shadow of a giant tree. This error might prove fatal; it’s imperative we find a water source today. To find a water source, I know we need to orient ourselves.

“How about the river next to our campsite?” Eddie asks.

I explain that Bear and Les are always on the move, always exploring terrain, and besides, a spring would be a much better water source than a river, less likely to contain giardia and other parasites. “The last thing I need is any diarrhea,” I say. (Bear, Sierra.)

We walk for two hours, climbing high above the river, past waterfalls, along a trail that plunges hundreds of feet to a watery chasm below. We turn a bend and hear a loud screeching. Three eagles, 30 feet in front of us, take flight. At least I think they’re eagles. They’re big, in any case. They fly. And they seem to be circling.

I grab a stick.

“If they dive-bomb, I’ll take the first one out with this,” I say to Eddie, who stares at me. Maybe he’s paralyzed with fear.

“They might be stalking us!” I tell him. “Grab a stick. We need to be prepared.”

“I don’t think eagles stalk people,” Eddie says. “Especially eagles in groups of three.”

“Yeah, ordinary eagles don’t. But what if these are rogue eagles? Have you thought of that?”

Eddie says nothing. Is this part of the silent assassin philosophy his kung fu masters have doubtlessly taught him? I appreciate Eddie’s laconic nature, and I don’t want to turn him into a chatty coward, but I wish he’d be more alert to the dangers that surround us. I feel responsible.

I’m about to tell him about the utter unpredictability of rogue animals when he pulls the book from his pack.

He reads aloud.

“The challenge of survival will therefore in all likelihood be easier to meet if you have a firearm and ammunition.”

I tell Eddie that’s a good point, but I don’t think guns are permitted here. Then we walk in silence for 20 minutes or so. We lose the eagles. We fall into a rhythm, and before long there are no sounds but the crunch of our boots. Eddie seems content. There’s a nice breeze. But things are quiet. Too quiet. A silent paradise can turn into a leafy nightmare in a single, terrifying instant. I know this. But does Eddie? He is so young. So naïve.

“One palm viper,” I intone. “One bush monster lunges out and, oh, man, I’d be in a mess of trouble then.” Les said the same thing in the jungles of Costa Rica.

“What’s a bush monster?”

I cough loudly.

“I mean, what’s a bush monster, sahib?”

“That’s a good question, Eddie,” I say, “and I hope you never have to learn the answer.”

Back in camp, I am weak from hunger, because I haven’t eaten since I had some avocado, cheese, dried apricots, and chocolate, which Eddie offered me and which I accepted only because I did not want to grow faint, and possibly stumble, and fall to my death, leaving my aide-de-camp at the mercy of dive-bombing rogue eagles. I’m feeling kind of faint again, so while Eddie searches for shelter makings, I think that for survival purposes it might be wise if I tried to catch a few winks in the late afternoon sunlight. Les did it in the polar-bear-infested Arctic, and I think Bear did it in the Scottish Highlands. I never saw Johnny Rambo rack out, but he must have.

When I awaken, Eddie has built a bed out of pine (or spruce) boughs. It is spongy and soft and fragrant. It looks just about as cool as anything Les or Bear ever curled up on. If not for the fear of bugs crawling all over me, and the gaping jaws of the man-flesh-eating bears, and my concern for family members and some friends who would be devastated if I were eaten just because I wanted to prove something about survival and manhood, I would have slept on it.

At sundown, I try again to make a fire using only my hard-earned television wisdom and my hippie survival tool, which, the elk handle notwithstanding, is a piece of flint and a piece of steel. Eddie has gathered a pile of kindling and some logs. I have constructed a tinder bundle of wood shavings and bunches of old man’s beard, which I have pulled off branches and which I know from Bear and Les is highly flammable.

I strike the hippie survival tool, and sparks fly into the tinder bundle. I strike again, more sparks fly. Lots of sparks, but no flame. Bear and Les always struggled with the sparks. Once they had the sparks, though, the flame naturally followed. I curse for two minutes, at which point Eddie suggests we use a match. I agree, but only because I don’t want to be responsible for a 16-year-old freezing in the backwoods. Also, I quietly nod and murmur, yes, I will in fact accept a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, and a few squares of chocolate, but only because I think it might emotionally scar my aide-de-camp if he witnessed his survival expert uncle go into spasms from protein deficiency. I think I read about that happening once. Why take the chance?

Next to the now-roaring fire, we sip water filtered from the river–with so many dangers lurking, we failed in our attempt to find a spring. Eddie leafs through the survival book and announces that we should have watched the eagles, tracked them to their prey, then stolen it. That way, we might have had fresh meat. Not a bad idea, I tell my pupil. Not bad at all. I need to get a copy of that book. The firearms chapter especially intrigues me.

Stars twinkle. Flames flicker. The mangy beasts in the trees doubtlessly watch us. I muse aloud about how–local, state, and federal legislation notwithstanding, and the ethics of killing such majestic creatures aside–I bet a nice roast eagle kabob would taste mighty fine right about now. Simply saying “mighty fine right about now” by firelight makes me feel woodsy.

Later, even though I technically sleep in the tent, emotionally and spiritually I am under the stars. It’s a subtle distinction, I tell Eddie when he asks why I’m not in the shelter he built.

My third morning, virtually alone, I realize that I need to find my way back to civilization, and that my best bet is to consult the wilderness compass.

“Or we could follow the trail we walked in on,” Eddie says.

He is so literal, so serious of purpose. Where is his sense of adventure? Is it too late for me to try getting him hooked on comic books? Maybe I can dig up my Man Thing collection and give it to him. His parents needn’t know.

We strike camp, pack, and hike out along the trail we hiked in on. I peer into the woods, at the crouching bears. Then I say, as Bear said when he left the Sierra, “I leave this area with a whole new respect for Native Americans and their survival skills.”

Eddie grunts.

A waiter approaches our table. An hour earlier, we had made it to the trailhead, barely ahead of the ravenous beasts. I promised Eddie as we drove back toward Portland that he could order whatever he wanted for breakfast and that I wouldn’t tell his mom if he had coffee. After he asks for French toast, and eggs, and bacon, and potatoes, and sourdough toast, Eddie buries his head in his survival book.

“Age-old skills keep my mind off ever-growing hunger,” I say. (Les, desert.)

Eddie grunts again. He’s so serious. I should probably be more serious.

“You did a great job out there,” I tell him, “especially on the shelter-building. And I really did sleep on the spruce boughs in spirit last night. Or pine boughs. Or whatever they were.”

“In spirit, sahib,” Eddie says.

I study Eddie’s face. Have I crushed his tender teenaged soul by not sleeping in the shelter? (“You really have to suck up the pain,” Les said in the desert, and I think about those words now, with remorse and some shame.) Was I too hard with the sahib thing? Could I have helped him have more fun? And could I have spent less time quoting Les and Bear and more time watching Eddie, emulating his quiet, competent ways? Most important, because I consider myself, like Les and Bear, a survival expert by training but a teacher by calling, did Eddie learn a single useful thing on this trip? Was I a total failure, not just as a woodsman but also as a role model? These are the questions I’m pondering when Eddie speaks.

“Sahib?”

“Yes, Eddie.”

“Next time we go into the unforgiving wild, can we build a death pit?”

Did he say “unforgiving wild?” I feel a warmth in my guts. Could it be the coffee?

“We’ll see.” I’ve decided it’s never too late to start speaking in monosyllables, to practice being strong and almost silent. Maybe this weekend I’ll install some drywall. I wonder what drywall looks like.

“We could use the pit to catch fresh meat,” Eddie says. “Plus, it would keep us safe from the gaping jaws of any ravenous predators who had developed an insatiable appetite for man-flesh.”

“I would like that,” I say. The warmth from my stomach has moved. Now it’s behind my eyes.

“They would be hopelessly doomed,” Eddie says.

I want to answer my nephew, but I don’t. I can’t. Words fail me. I am saved.

Years ago in Yosemite, writer at large Steve Friedman slipped to the edge of a yawning precipice, then–inch by inch–manfully pulled himself to safety.