How to Fear Less

'Photo by Patrick Heagney'

I kept it together all the way to the Ledges. I’d hiked five miles from the Longs Peak trailhead, rock-hopped through the Boulder Field, and paused at a notch in the granite, the famed Keyhole, with a view across the alpine zone of Rocky Mountain National Park. Then I crouched, took a deep breath, and turned to face a howling wind—toward the crux of the journey.

I had studied what comes next: Follow a series of spray-painted bulls-eyes, then shuffle across the Ledges, a hundred-yard section where the route pinches into a gully that leads to a granite catwalk over a thousand-foot drop. By all accounts the exposure is attention-getting, but it’s not a technically hard traverse. Thousands of hikers climb the Keyhole route every year. Grade-school kids have stood on the summit. Like many Fourteeners, it’s a life-list ascent that requires equal parts fitness and confidence.

My body is fit enough, but my mind is consumed by fear as soon as I see the Ledges. My body spasms. My neck muscles clench into cables. My mouth tastes like I’ve been sucking on pennies. I have the feeling that I will die, right here.

But I can’t just turn around and skulk my way back to the Keyhole. I’m here with my new coworkers—I’ve just taken a job at this magazine, in fact—and I want to prove I am who they think I am. No one else seems the least bit troubled. I stare at the wall ahead, trying to break the climb down into moves, trying to visualize going through the sequence. But the longer I look, the more I become convinced that I’ll grope at the wall, slip, cartwheel down the gully, hit the ledge, and ragdoll through several hundred vertical feet before twitching myself to death, hair matted with blood.

Someone yells “climb!” and I step to the rock like the condemned to the gallows. I see myself flop a geoduck palm onto the face and lift a limp foot. I see my boss step up behind me and help me to the top by pushing my butt. And then I see the Narrows, a sidewalk-wide shelf embroidered to a vertical rock face. I want to stop here, curl up, fake a migraine—anything to stop climbing. Instead I ask my boss to hold my hand and watch myself plod on to the summit, joyless and robotic.

This is no way to live.

Just about everyone experiences fear—it’s a safety mechanism coded into our brains that helps ensure the survival of the species. To be afraid is to be human.

There are certain things that most of us find scary. Some, like snakes and spiders, scare us because they violate our “prediction systems” (they move erratically), says Margee Kerr, Ph.D., a sociologist and author of Scream: Chilling Adventures in the Science of Fear. Other things, like falling, scare us because they can—and sometimes do—end in death. But how we react to that stimulus is where things start to diverge.

Fear lives in the oldest parts of our brains, a pair of almond-shaped clusters of brain cells and neurons called the amygdalae that act like a watchtower over the body. When a life-threatening stimulus appears, the almonds override the thinking brain and enter survival mode. “This triggers the release of adrenaline and norepinephrine,” Kerr says. “These increase heart rate, kick metabolism into high gear, and make you burn sugar faster”—fight or flight.

For reasons that aren’t clear, the same stimulus can produce different reactions in different people, and each person’s fear profile is about as unique as her fingerprint. At the benign end of the spectrum, there’s sweaty palms, increased heart rate, and slight shortness of breath—standard anxiety response. Panic attacks sit at the severe end of the spectrum, and that’s where I’m at with heights. In effect, my amygdalae turned Longs into Everest. (Phobias are a different beast: Phobics often were affected by some type of trauma, and react to the idea of the thing that scares them as strongly as if it were the actual thing.)

After my meltdown on the mountain, when my coworkers celebrated while I obsessed about how I was going to die on the way down, I decided it was time to get help. I was missing out on too much. The mountains. Experiences with friends and coworkers. My sense of self. I hadn’t always been afraid of heights. I had once climbed in the Tetons and had fancied myself a budding mountaineer. But somehow my fear had grown unchecked, and now I could hardly remember the woman I’d been. My bad day on Longs made me realize how much my world had shrunk. This is the common experience of those who suffer from regular outdoor fears—such as fear of lightning, getting lost, and bears. In effect, the fear walls off the outdoors.

Treatment for excessive fear and phobias can be effective. There are a lot of techniques and variations, but they all center on replacing that overblown response with a calmer, more measured reaction (usually through a technique called cognitive behavioral therapy; sometimes with an assist from antianxiety meds). That reprogramming, paired with exposure to the fear, recalibrates the comfort zone into the normal range. But while this treatment has a good track record, it’s a slow process with no guarantees.

The good news is that there are a lot of new treatment types just starting to gain recognition and use.

The bad news is that there is no one set treatment path that works for everyone. What’s effective for one person may do nothing for another, and there’s really no clear way to know where to start. Most doctors and therapists use a mix of techniques. Trial and error looms large. And, according to Kerr, you have a limited time to fix your problem. Neuroscientists believe that the brain remains plastic enough to easily rewire until roughly around the age of 50, at which point gains are harder won. By the time I decided to seek treatment for my fear, I was already 41, and I felt a sense of urgency I hadn’t expected. It had taken a decade to get this bad. What if it took that long to cure?

My search for a quick remedy led me to something called brainspotting. I read up: not a lot of research, but 8,000 therapists are registered in its use worldwide. Good enough. I parked myself on the futon of Boulder, Colorado-based hypnotherapist Julisa Adams.

Brainspotting, Adams explained, is a “powerful method of psychological healing that works by identifying, processing, and releasing deep neurophysiological sources of emotional or body pain” that the conscious mind, for whatever reason, has trouble accessing. Brainspotting practitioners believe it’s most effective when paired with bilateral sounds (tones that alternate between a set of headphones), which appear to alternately stimulate each hemisphere of the brain. Any life event that causes significant physical or emotional injury or distress is fair game for brainspotting, from chronic pain to sexual abuse to social problems. But what I cared about was that brainspotting (supposedly) works one-session fast. And what’s better than sloughing off a decade-old fear in the time it takes to break camp?

The idea is that eye positions—where you hold your gaze when you’re thinking about something—correspond to emotions. Simply by moving eye positions—and talking through your feelings with a therapist—you can change your brain’s association from a bad one (freaking out on a mountain, say) to a calming one (cuddling with a loved one). “We’re still not sure why,” Adams said, “but when your eyes dart back and forth, the brain clears itself.”

The whole thing sounded about as scientific as snorting colloidal silver for a head cold, but at Adams’s prompting, I recalled my worst moment on Longs and observed where my eyes went (level, to the left). As I held them there and told Adams about my experience, my heart rate spiked, my palms started leaking, my bowels gurgled.

Adams then asked me to think of something comforting (my “resource spot”). My brain whisked me away to a mountain bike ride (my happy place), and my eyes tracked up and to the right. We then talked about why this memory felt comforting—no crazy exposure, biking is something I excel at, and the flow of riding just makes me happy—and, weirdly, while I held my gaze there, I did feel calmer.

We repeated the process a few times. Then Adams said, “OK.”

“OK? So … I’m cured?” I asked.

“Well, we’ll have to see, but I used brainspotting on a young boy with a debilitating fear of the dark. After one session he claimed he’d never been afraid.”

I imagined myself on Longs, stopping the whole group: “Um, guys? Can you hold up? I need to access my resource spot real quick.” The vision made me want some insurance, and fortunately, there’s another quick-fix treatment that’s gaining traction.

So I returned to Adams’s futon. This time she tried something a little more proven, if only slightly less kooky-sounding. It’s called the Emotional Freedom Technique and it’s based on acupuncture, only you use your fingertips instead of needles. And unlike brainspotting, this one has clinical trials that showed a significant improvement in how study participants handle stress, as measured by the cortisol in their saliva. Three separate studies found that a single session of EFT was enough to unspool a phobia completely.

According to the theory, the combination of gently tapping certain pressure points while thinking about your specific problem and speaking positive affirmation clears emotional blocks. The key, Adams told me, is to think about your problem before you tap. You’re instructed to come up with a positive affirmation that “acknowledges the problem” yet “creates self-acceptance despite the existence of the problem.” Sure thing.

We started with an affirmation statement fitting the following rubric: “Even though I have a fear of [blank], I love and accept myself unconditionally.”

I filled in the blank with “heights.”

“Now,” said Adams, “tap.”

I closed my eyes and gently hit my nine tapping points (“meridians”), including the top of my head, eyebrows, sides of my eyes, under the eyes, under the nose, chin, collarbone, elbows, and wrists. Crazily, my mood went from charged up, antsy, and anxious to calmer and more confident. The more I tapped, the better I felt about the thought of climbing. Sure, I was sitting inside, on a level floor, but I experienced the tiniest flicker of hope that I might be able to approach an exposed ridge and scramble up it.

Was I cured? Only one way to find out.

On a hot August afternoon, I set out for Blob Rock, a crag outside of Boulder. With the help of two expert climbers, I intended to rappel down to a tiny ledge in the middle of a 400-foot-high rock face. Once there, I’d be clipped to an anchor for safety and left on my own for an hour. If my quick-fix treatments had worked, I’d know soon enough.

I had Adams’s words ringing in my ears that brainspotting might have worked in one session. But I hedged just in case, tapping a few meridians before getting out of the car. I then hiked to the top of Blob Rock and clipped in to a rope. On the walk to the edge, I felt all the normal stuff: clenched neck, speeding pulse, taste of metal. But maybe—just maybe—it was a little less intense, because I didn’t want to run away. Instead I turned around, leaned away from the cliff, and slowly lowered myself (on belay) to the 4-foot-wide ledge. I was surprisingly calm in motion, and stayed calm while I waited for one of the climber-helpers to lower down and secure me to the anchor. When he left, for a few short minutes I remained at ease.

But fear operates on its own schedule. I looked across the canyon and saw two climbers on another route. The horizontal distance somehow tweaked the vertical distance below me and my equilibrium went terribly out of whack. My head started to spin, so I took a deep breath and tried tapping: “Even though I have a fear of heights, I love and accept myself unconditionally.” I forced my eyes into their resource spot, but looking up made me feel worse, and I knew brainspotting wasn’t the miracle I was hoping for. And then I realized I wasn’t holding on to anything.

I felt like Wile E. Coyote after running off a cartoon cliff, suspended in midair with a split second to contemplate my fate. When I looked at the slings securing me to the anchor, it was with different eyes. There was no way they’d hold. My limbs went limp. Suddenly, I could see myself slipping off the ledge, cartwheeling through space.

I survived an hour on the ledge, but it didn’t feel like a victory. My anxiety redlined and stayed there, and I realized that I could check another fast-fix method off my list. It’s called flooding, and can be thought of as “the just-suck-it-up-and-get-over-it treatment.”

There are two schools of thought when it comes to facing your fear head-on. The slow lane, called desensitization, and the fast lane, flooding. (Slow: Show a person who is terrified of snakes a picture of a snake. Fast: Throw him into a snake pit.) Kerr, the fear expert, says the scientific community supports desensitization while it is split on the benefits of flooding.

I knew which side I was on after an hour on that ledge. Instead of flooding or brainspotting or tapping my way to happiness, I clenched my quads so hard throughout the ordeal that they were sore for days.

A year went by. Life, work, and being a mom to a newborn all crowded out my quest, but that makes sense given my fear is strictly recreational. Ignoring this fear came at little cost to my regular life. But another year meant my fear was another year closer to being permanent. At least the break might work in my favor, I hoped, imagining new advances in the field.

The most cutting-edge lab-based fear research being done today is with virtual reality. In essence, VR lets facilitators bring the fear indoors and carefully customize your exposure to it. It’s desensitization with complete control.

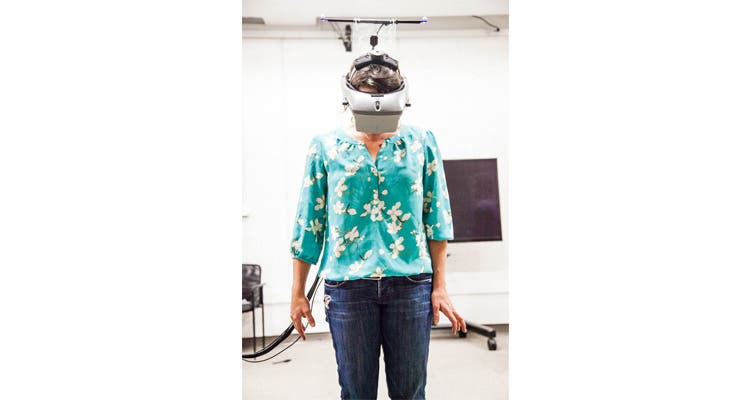

One September day, I drove to the University of Utah’s acrophobia-specific VR lab to meet with lead researcher Jeanine Stefanucci. Stefanucci and her team were investigating how the physiological experience of heights in virtual reality compares to the real world, to gauge VR’s viability in exposure therapy. Real-time biofeedback provides researchers and therapists with a patient’s vitals, including heart rate, respiration, skin conductance, temperature, and electrocardiogram. Theoretically, it provides the tools needed to mitigate the fear response, and patients have reported an increased ability to keep their fear in check in the real world.

When I traveled to Utah, I was too early; Stefanucci’s research was still preliminary—the university hadn’t created a protocol to use VR for heights yet—but she let me try out the equipment anyway. I put the goggles on and found myself on a plank between two tall buildings. If I stepped off, ostensibly, I would fall to my death. But while the image made me feel dizzy, I couldn’t suspend my disbelief enough to stop feeling the floor beneath my feet. I wasn’t actually about to die, and knowing that changed my reaction. I’d later learn this was common—the VR heights world simply wasn’t realistic enough—but developers are making strides. Virtual-reality treatment is now used by 50 or so specialists around the country, but recent leaps in the quality of the VR worlds suggest it may be coming soon to a therapist’s office near you.

But it wasn’t ready for me that day, so I turned to an older, more conventional method: cognitive behavioral therapy. CBT looks at how we think about a situation, and how this affects the way we act. It’s used most commonly on people with depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, panic attacks, and PTSD. In CBT, patient and therapist discuss specific disorders and set goals to manage them. In my rush to find a quick fix, I’d avoided this sort of hash-it-out, slow-boat treatment event though it’s recognized as one of the most effective ways to treat fear. So on the Utah campus, I met with Steven Ross, a psychologist who treats mood, anxiety, and substance-abuse disorders.

Ross (no relation) sat me down in his office and asked me to think about climbing and heights and tell him the first words that popped into my head.

“That I’ll fall and get hurt,” I told him. “That I’ll die.”

“So that’s the cognitive part,” he said. “The words that rattle around in your head, the what-ifs that feed the anxiety. Part of the treatment in cognitive psychology is examining and modifying these thoughts so they don’t feed your fear.” Essentially, he was saying that I could change what my brain was telling me and slip out of the story that inevitably ended in my death. Practically, he suggested I develop a mantra that would guide my thoughts in a good direction.

“The second part,” he continued, “is gradual exposure and small steps while you try to maintain some degree of relaxation.” I told him about the flooding experiment and he looked at me sideways. “There is some literature that suggests flooding is useful,” he said. “But to me, it’s like giving someone a root canal without Novocaine.” Yep.

“The key is to take baby steps,” he said, “going to the edge of your fear, hanging out for a while, and then backing off.” OK, desensitization.

But the last thing he said gave me the biggest boost of confidence yet: Just by trying to address my fear I was participating in an act of bravery. The fact that you get scared doesn’t make you a coward.

The next day, I stood at the base of Mt. Superior. It’s 11,040 feet tall and the ascent alternates between class 3 and 4 scrambling with a little class 5.

My friend Sandra and I started up its steep lower flank in a light drizzle. We picked our way up a long and loose scree field that terminated at a steep, polished-rock gully. I was fine until we came to a place where I had to stem across a small chasm. Here, my brain filled with images of falls and snapped tibias.

That part was normal. What changed was my response. I stopped, leaned against a rock, took some deep breaths, and repeated the mantra I’d adopted at Ross’s suggestion: It’s all good, it’s cool. I like climbing. I’m a climber. And, to my surprise, I caught the full-blown panic before it ignited. I identified a point of exposure I was OK with, and the point beyond, and knew that if I went farther I’d probably go to pieces. So I stopped where I was, not even close to the summit.

Turning back actually felt like a success. Ross was right: The confidence that I’d gotten from going to the edge and hanging out made me want to do it again. My fear wasn’t gone, but I felt like I’d made progress.

The only problem was that this was the slow-lane method and I was another year older. Every year that went by, the problem became more intractable. (Plus, patience isn’t my strong suit.) Fortunately, I had an idea of how to speed the process along.

I knew just where to go: the Tetons. About 10 years ago, when I’d been a different woman who knew nothing about a fear of heights, I’d scaled the Grand Teton with Exum guide Nat Partridge. He’d taught me to lead climb on another trip and I was sure he’d be the right guy to restore my confidence and comfort in the mountains.

But after I explained why I needed his help, Partridge seemed oddly formal on the boat ride across Jenny Lake. From the dock, we began the slow, mud-slick hike to the base of Exum’s practice crag.

Right there, Partridge shoved his hands in his pockets. Turning to face me, he said, “I don’t think I can help you.”

“What?” I stammered.

“I can’t.”

“But my fear!” I yelped. “It’s gotten bad. I thought… with a refresher…”

“I can’t help you,” he said, “because you already know what you’re doing.”

“No, I don’t!” I said. “I’m telling you, I have a problem.”

Then he recalled the times we had climbed together: “It wasn’t like guiding at all, because you and your husband were both so comfortable.” He also said he put me the farthest from him on our climbing rope on the Grand because I was our team’s strongest climber.

I stared.

“You don’t have a problem with heights,” he said. “You’ve fallen into the trap of so many Americans. They—we—all think we’re in need of curing. But when I see you, I see someone strong, capable, and confident. If you want to climb, you should just put in the effort to learn how to do it.”

Instead of getting defensive, I felt better. This was just what I needed to hear. When Partridge talked of seeing my strength, he helped me see it. Kerr later explained how this worked, saying, “When someone we trust gives us the ‘rewarding and affirming smile,’ our cortisol levels drop, we calm down, and we are better able to handle stressful situations.”

For the rest of that day, Partridge and I didn’t talk about fear of heights. We simply climbed. At the top of each route, we hung out over a hundred feet of exposure. This was way beyond what I expected: Not only had I made another step forward, I swear I felt my brain changing. Maybe I’d taken the slow lane, but the pace felt right.

My success in the Tetons felt good, but I knew by now not to expect too much too quickly. I still couldn’t say for certain how I’d react on a climb without someone there to tell me I could do it. I decided to test myself on the half-mile-long, class 4 ridge between North and South Arapaho Peaks in the nearby Indian Peaks Wilderness. It has the exposure of Longs Peak but the scrambling is actually harder, making it a perfect way to measure how far I’d come since that fateful day I’d started my quest.

Three friends joined me on the two-hour hike to the base of the ridge. Ascending amid aspen leaves crisping in the autumn sunshine, I couldn’t help smiling when I recalled my first attempt at an instant cure two years earlier, with brainspotting. Though I’d proven that the slow lane was the only lane for me, my sense of urgency had not decreased—I was that much closer to 50—but now I was better equipped to accept uncertainty.

Rewiring the brain is a complicated undertaking, and even scientists don’t fully understand it. “So many factors go into how our brains react to stress, such as genetic makeup, epigenetics [how the environment influences what genes we express], and the constantly evolving effects of nature and nurture,” Kerr says. “While it’s sexy to think that we can go in with a machete and create a different outcome, it’s really, really hard, and takes constant vigilance.”

But at least this much is clear: Tackling fear is important, regardless of how long and complex the process. You’ll likely try multiple treatments and probably get frustrated. It’s OK. Persevere, even if it takes years, because the payoff is multifaceted. Neurologically, facing fears increases our confidence, and each positive experience imprints on our brains, reinforcing our resilience. The bottom line is it feels good to feel good. And the biggest benefit of all is access to a larger world.

That thought crystallized for me when we arrived at the Arapaho Traverse. It was windswept, draped in patches of snow, sharp, and delineated by a line of serrated granite. I couldn’t believe I was just attempting it for the first time, though it lies just 15 miles from my house. My world was getting bigger already.

I gazed across, took a deep breath, and repeated my mantra. The old fear rose up, but so did a feeling of confidence. I stepped out onto the narrow ridge with certain-death falls on both sides. No guide, no rope, no one holding my hand.

Was I totally cured? No. But I went forward instead of back.

Tracy Ross lives in Nederland, Colorado, with her husband, two sons, and daughter—all of whom are fine with heights.