How to Hike in a Heat Wave

'Whit Richardson'

1 ) Drink what you need.

Stop for water when you’re thirsty, Myers says, but don’t force fluids—everyone has different water needs (though a good baseline is a half liter per hour at 80°F, and a liter per hour at 100°F). Like dehydration, which affects most endurance athletes on some scale, hyponatremia (diluted salt levels due to overhydration) is a serious risk: It affects 10 to 30 percent of athletes, according to some studies.

2 ) Eat carbs.

Heat and humidity can mess with your appetite, but remind yourself to stop and eat every hour, focusing on carbs, which convert to energy faster. Instead of choking down bars, bring foods you know you enjoy (Myers favors junk food), and consume salty snacks at every water break.

3 ) Get wet.

Cool down with artificial perspiration—put a damp bandana on your neck, and soak your shirt if it’s really hot (cotton’s absorbency makes it a good pick for extreme heat) to enhance evaporative cooling.

4 ) Protect your skin.

Melanoma occurs most often on the legs (for women) and torso (for men). Apply sunblock every three to four hours (include your scalp, ears, and the backs of your hands). Safer bet: Wear a broad-brimmed hat and UPF-rated clothing, which has more tightly woven fibers and/or UV-blocking coatings and dyes.

5 ) Take breaks.

In temps above 90°F, stop to eat, drink, and rest for 10 to 15 minutes for every hour of exertion. Look for spots in deep, all-day shade rather than creating shade with a tarp or tent.

6 ) Heed the symptoms.

Feeling ill? Stop and cool off by dripping water on your head and torso. Then determine whether too much or too little water is the issue (symptoms are similar, but think about your ins and outs over the past few hours) and treat accordingly: salty snacks for hyponatremia, water for dehydration. Nausea, vomiting, disorientation, and fainting could mean heatstroke or heat exhaustion. Seek medical care.

Quench Your Thirst

Your body uses water to maintain blood pressure, regulate temperature, and lubricate joints to help prevent injury. Mild dehydration—as little as 2 percent of your body weight—can compromise hiking performance. Losing 5 percent can shut you down altogether.

You lose .8 to 3L of sweat per hour

To precisely calculate your hydration needs, weigh yourself before and after a one-hour hike in conditions similar to those of your planned trip. Each lost pound corresponds to half a liter of water.

How to Hydrate Better

The easiest way to determine if you’re getting the right amount of fluids? Pay attention to your pee.

| Frequency | What it means |

| Every 15 mins | Too much |

| Every 3 to 4 hours | Just right |

| Twice a day | Too little |

Case Study: Dehydration

Eddie “Oilcan” Boyd, 21, was hospitalized for dehydration while thru-hiking in 2016. He’s since learned to hydrate right and finished the Triple Crown.

I started the PCT in May of 2016 with a 20-mile day from the Mexican border to the Lake Morena reservoir. Being from Ohio, I’d never experienced desert exposure. I brought 4 liters of water for the day, but could’ve easily used 8. About halfway through the 1,200-foot climb up Hauser Canyon, I ran out . That’s when I started getting weak. Each step was labored, and I was dizzy and disoriented. Every five to 10 minutes, I had to sit down and catch my breath.

My buddy gave me a half-liter, but I ran out again at the top of the canyon. I laid down for almost an hour. It felt like someone had given me melatonin, but we had 3 more miles to Lake Morena. I barely stumbled through them.

In camp, I slammed a liter, then threw up after two or three bites of dinner. Next day, I was still vomiting and couldn’t keep water down. Some hikers dragged me the 10 miles to the next town so I could get help: an ambulance, an IV, and a rest day.

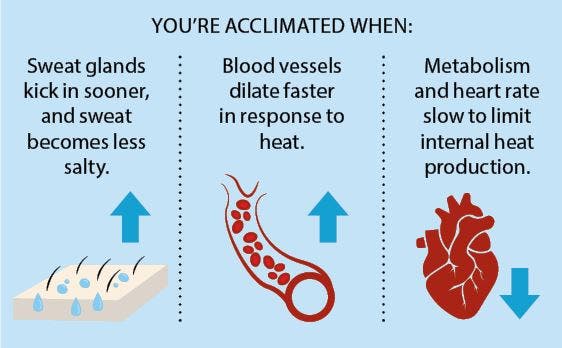

How to Acclimatize to Hot Weather

Altitude’s not the only thing that takes some getting used to. Train your body to resist overheating, stay comfortable longer, and avoid heat-related illness.

Get a head start.

Begin acclimatizing between 10 and 14 days before a trip. Adaptations will stick around for a week or two.

Train in the heat.

The best way to acclimatize is to simulate the conditions you expect. To achieve this gradual increase, you’ll need to schedule your hikes accordingly (early, midday, etc.). Start easy with moderate hikes in mild temps (70°F to 80°F) every other day. Then, within 10 to 14 days, work up to daily one- to two-hour runs and strenuous hikes at 90°F and up.

Add layers.

Training up north or during shoulder season? Layer up to spark your sweat glands, or exercise indoors and dial up the thermostat (or hit the sauna; see below).

Let off some steam.

Studies show that stints in a sauna or hot bath can trigger adaptations. Start with a 10-minute session and add 5 minutes each day until you can handle 30 to 45. (Drink plenty of water and don’t push it—cool down as soon as you start experiencing headache, fatigue, or other symptoms of heat illness.)

Troubleshoot your nutrition.

While training, experiment with different foods and sports drinks to determine what appeals to you in extreme heat—you might not want your customary Snickers in triple-digit temps.