Case Study: Lost in the Gila Wilderness

'This story's hero: Ross Mason, 44.'

This story’s hero: Ross Mason, 44.

Build an emergency fire. (by Supercorn)

Topo symbols can help you orient your map. (by Supercorn)

![BootFix445x260 32134 See step [15] for a quick boot fix. (by Supercorn)](https://cdn.backpacker.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/bootfix445x260-32134.jpg?width=3840&auto=webp&quality=75&fit=cover)

See step [15] for a quick boot fix. (by Supercorn)

[1] Mason studied a guidebook, reviewed maps and online trip reports, and called ahead to ask rangers about trail conditions.

[2] Target back, core, and leg muscles. Good cardio fitness is also key—boost workout intensity by wearing a weighted pack.

[3] He had warm clothing and his sur- vival kit included a knife, whistle, and headlamp. Item missing: signal mirror.

[4] Solo hikers are prone to heavy loads. Streamline essentials to lighten your pack without compromising your safety.

[5] Choose a reliable friend who will be available during your entire trip. Give rangers your contact’s info when you check in.

[6] Smart move: Overnighting at a mid-elevation site (Mason camped at 5,700 feet) helps acclimatization.

[7] Mason had plenty of fuel, but the hassle of boiling water reduced his intake and contributed to dehy- dration. Carry lightweight chemical tablets as backup.

[8] After months of planning, he didn’t want to downsize his route. Avoid disappointment by planning several hikes in the same area.

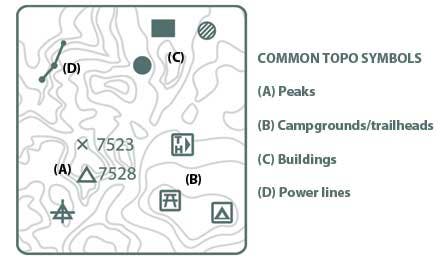

[9] Mason should have been checking his map as he hiked, comparing man- made and natural landmarks with navigation-aiding symbols like: peaks, campgrounds or trailheads, buildings, or even power lines. (See Illustration above).

[10] He lost 10 percent of his body weight due to dehydration. Even a five percent drop reduces endurance and can cause disorientation.

[11] Mason carried a compass, but didn’t check it. Check yours regularly.

[12] Good idea: Mason wasn’t sure of his location. Staying put over- night reduced his risk of becoming more lost.

[13] If conditions are safe for a small fire, build a smoky signal: Clear the surrounding area (at least five feet in every direction) to dirt. Create a dry tinder base, surround it with a green wood frame (like a log cabin), pile the structure with green branches and leaves (it should be less than three feet high), and light the tinder inside.

[14] His dehydration was severe. In most survival scenarios, dehydra- tion poses a more serious risk than illness from contaminated water.

[15] Repair a separated boot sole by wiping it clean and binding with duct tape. Bring at least 25 feet wrapped around a trekking pole or water bottle.

[16] He laid out a blue jacket and put notes at a nearby junction.

[17] Helicopters can only land in designated wilderness areas for life-or-death rescues, but pilots will signal that they’ve seen you.

[18] Search teams often check buildings, trails, and power lines early in the rescue process because as many as 72 percent of lost hikers are ultimately found near man- made and linear structures.

[19] Backtracking would have been Mason’s best option, but his odds were poor given his poor physical condition, broken boot, and the waterless terrain.

Ross Mason was an experienced hiker, and he carefully planned [1] the 25-mile route for his solo three-nighter in New Mexico’s half-million-acre Gila Wilderness. He knew that the rough terrain—7,000-foot plateaus and canyons flanking the Middle Fork of the Gila River—would tax him (he’d be coming from sea level), so he trained for weeks [2] and packed his standard gear [3] along with a few extra meals and stove fuel for six days. [4] Finally, before leaving home, he asked his co-worker Jill to be his emergency phone contact. [5] He promised to call her when he finished the hike.

Friday night he car-camped near the trailhead, [6] and he began hiking on Saturday morning. Within a few hours, his water fil- ter broke. “I decided I would just boil my drinking water,” [7] Mason says. Later that day he crossed an alternate trail that returned to the trailhead, but he decided to continue with his original plan, [8] despite the broken filter. He hiked a total of 12 miles to his campsite. The next morning, he climbed to a plateau where he missed the crucial trail junction to return to his car. He didn’t realize his error or stop or consult his map. [9] He continued across the waterless landscape, thinking he was on track, while becoming increasingly dehydrated. [10]

It wasn’t until Monday afternoon—when he should have been finishing his hike—that a signpost near a boarded-up cabin exposed his mistake. Instead of indicating one mile to his trailhead, as he expected, the sign said it was 18 miles away. Mason was stunned. “I had no idea what direction I’d been hiking in for the past two days.” [11]

He impulsively started down the 18-mile trail, but it was dusk and the tread disappeared along the canyon bottom. He stopped, [12] realizing that getting further disoriented in unfamiliar terrain was risky. Mason set up camp to wait until morning. On Tuesday, he heard a small plane and climbed up a ridgeline to make a signal fire. [13] Uncertain of his location and his ability to navigate, Mason decided that waiting for rescue was the safest way to proceed. Despite being just 18 trail miles from the trailhead, he was completely disoriented. By Wednesday afternoon, he hadn’t spotted any additional planes, and he was weak from dehydration and exposure. [14] With storm clouds gathering on the horizon, he retreated from the ledge to find shelter. Halfway down, the front of his boot peeled off. Mason limped toward the locked-up cabin he’d seen the day before to try to repair it [15] and wait for rescue. On Thursday morning—three days after his trip should have ended—he was so lethargic that it took him all morning to set up more signals in a field. [16]

That afternoon, he heard a helicopter and waved frantically at it. Certain he’d been seen, Mason waited for the chopper to return. [17] On Friday, he awoke to find rescuers approaching.

How’d they find him? When Mason hadn’t contacted Jill or the Gila rangers by Tuesday, both parties noted that he was overdue and contacted each other. The rangers located his car, and the search for Mason began. Forty-eight hours later, the helicopter crew saw him outside the cabin. [18] If he hadn’t been rescued, Mason says he would have tried to walk out, but he was so dehydrated that his chances of making it would have been slim. [19]