What New Offshore Drilling Means for National Parks

'Richard A. Weaver'

Sediment from the Appalachian Mountains washing into the Gulf of Mexico for a million years has sprouted a chain of barrier islands off the coast of Florida and Mississippi that provide habitat for sea turtles and shorebirds. Dolphins are so common that local kayakers compare them to pigeons.

The National Park Service manages these islands as the Gulf Islands National Seashore. They’re among New Orleans-based wetlands ecologist Mark Ford’s favorite places to explore with his three teenage sons. That’s partly because he’s concerned that by the time his boys are his age, at least half of these islands won’t still exist; rising sea levels are washing them away.

Climate change isn’t the only potential threat to these islands. Offshore, just far enough that they’re not visible from the mangrove and cypress marshes , are oil drilling platforms. The inevitable risk posed by that activity washed ashore in 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig and sank into the Gulf of Mexico, killing 11 workers and releasing 4 million barrels of oil over 87 days.

Efforts to contain the spill saw workers setting fire to oil in the gulf and in marshes it had covered to burn it off and reset the ecosystem. Residents as far away as New Orleans could smell the smoke. Volunteers walked beaches with nets the size of lacrosse sticks and hand-sifted globs of oil from the sand. Some was vacuumed out of the water, some sprayed with a dispersant that sank it to the sea floor.

“It was insane, truly insane,” Ford says. “There was a lot of oil. … They were hauling it out by the ton in places.”

Allowed to remain, it would have killed the plants and their roots, poisoned the sediment and the vertebrates living in it. Restoration would have required scraping and rebuilding the area from the soil, at a price of at least $100,000 per acre.

The Deepwater Horizon disaster was the worst-case scenario and one of the most notable spills in the nation’s history, though small spills are so routine that some Gulf Coast states maintain a full-time staff to manage their clean-up. Now, a new proposal by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management to open a total 98% of the outer continental shelf for oil and gas development has coastal parks and recreation areas nationwide asking if they could be next.

“It’s massive in scale, and in that regard it’s unprecedented,” says Mike Murray, a park service retiree who spent 34 years working in Everglades National Park and at Cape Cod and Cape Hatteras National Seashores. He now volunteers with the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks. “It just seems like it’s a broad, massive proposal that’s not been well thought-out.”

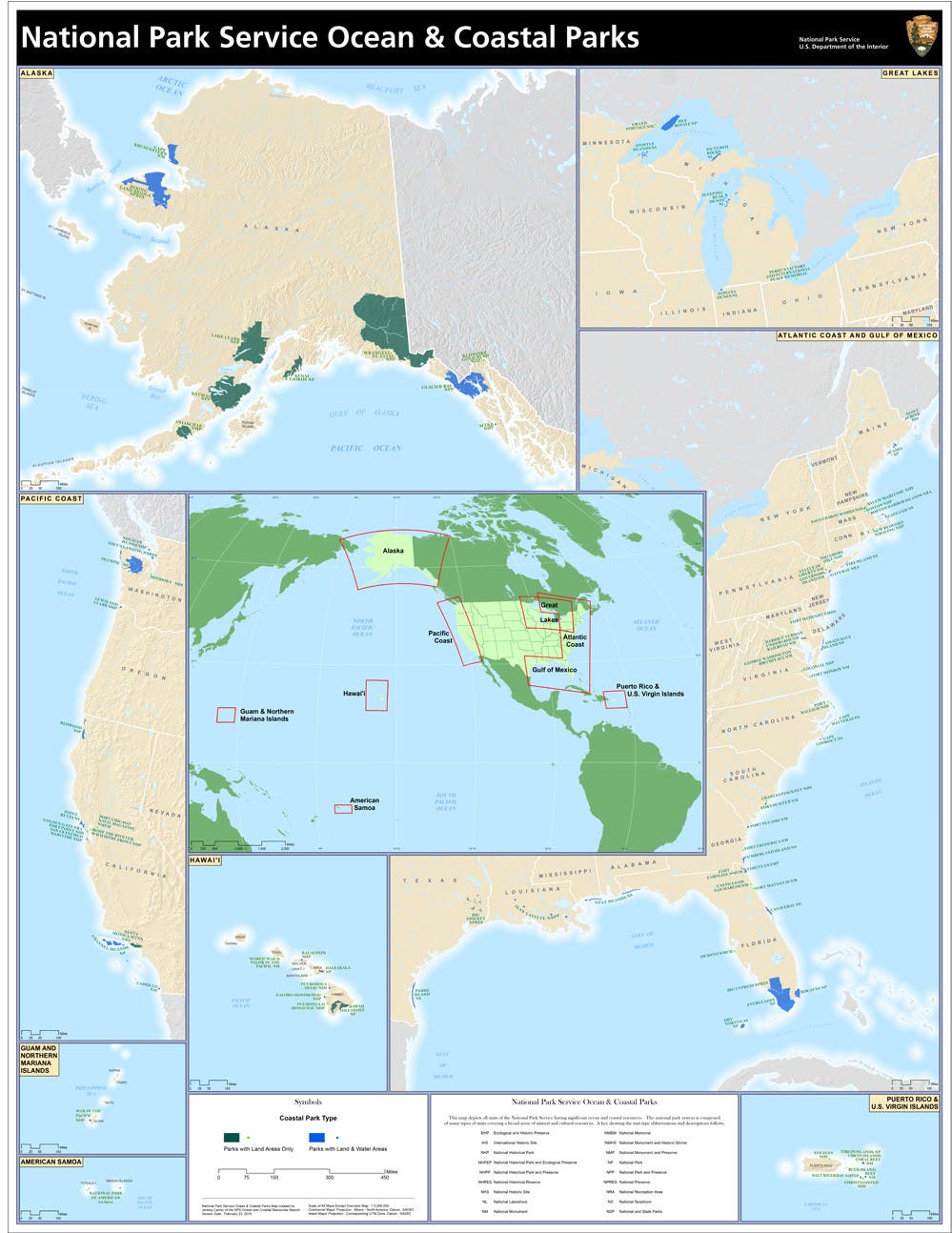

Murray tallied 67 coastal park system within range of the proposed leases, as well as 10,000 miles of shoreline and 2 million acres of marine waters. In 2016, those parks saw 85 million visitors who spent $4.5 billion locally.

The nightmare scenario now is oil washing ashore at Acadia or Olympic National Parks or coating beaches in California or at Cape Cod, says Nicholas Lund, senior manager of the National Parks Conservation Association’s landscape conservation program.

As an alternative, Murray argues for the approach he saw the bureau use when developing a proposal for offshore wind development near North Carolina. “Smart from the start” was the motto then. Local input steered the agency away from erecting 600-foot-tall windmills in military training areas, shipping channels, bird migration corridors, and scenic vistas.

“When I see what they’re doing on this offshore oil and gas proposal, it’s like night and day,” he says. “Instead of BOEM doing the thinking ahead of time—where do we have high conflict areas, where do we exclude—they’re going to put the pressure on the public to do their thinking for them. I kind of object to that. I think the agency’s legal and moral responsibility is to do some of the thinking ahead of time.”

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s response: there will be careful examination of any new drilling sites. In an email, Tracey Blythe Moriarty, deputy chief and media manager for the bureau’s office of public affairs, explains that this is the start of a years-long process, beginning “with the broadest consideration of areas available for leasing,” then moving through environmental reviews and detailed assessments of plans including well locations and drilling vessels.

“In a mature area such as the Gulf of Mexico, it generally takes 5-10 years from the time a lease is issued before production begins,” Moriarty writes. “In a frontier area where leasing has not occurred in many years, or perhaps ever, the time would likely be longer depending on the challenges presented in the area.”

The proposed program allows for examining areas that have not been analyzed under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act or National Environmental Policy Act in decades.

“This information will increase our understanding of the resources available on the [Outer Continental Shelf] and the potential impacts were they to be offered for lease,” she continues. “The Secretary [Ryan Zinke] would like to see this analysis to inform decisions on areas to be included or excluded from the National [Outer Continental Shelf] program.”

The bureau has already received more than 12,000 comments, and will take them until March 9. Based in part on comments received, the bureau expects a strong interest in the Gulf of Mexico—where a post-Deepwater Horizon moratorium is set to expire in 2022—as well as Alaska’s Chukchi and Beaufort seas and the mid- and south-Atlantic.

Whether this development would be visible from on shore is hard to say, Moriarty writes, but would be considered. Onshore development could include pipelines, processing and support facilities like ports, and food and marine transportation services. Those impacts will also be considered in the Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement, which is being developed at the same time as this program.

Asked about how the bureau would respond to concerns about incidents like Deepwater Horizon, Moriarty writes, “There is inherent risk in drilling for oil and gas, which is why BOEM [Bureau of Ocean Energy Management] and our sister agency Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement work with our government partners and other key stakeholders to ensure the best science and engineering are used to inform the safety and environmental requirements applied to [Outer Continental Shelf] energy development activities.”

Opposition to this plan has come from governors up and down both coasts and congressional representatives on both sides of the aisle. If the national monument review—which saw the Department of the Interior recommend changes to monuments despite an overwhelming majority of comments expressing opposition to it—is a barometer, public opinion may not be enough to change their course. Still, the National Parks Conservation Association is asking for an extension to the 60-day comment period and meetings beyond those already scheduled.

“The folks in these areas don’t want it, Americans don’t want it, park communities don’t want it, and we need to tell Zinke that,” says Lund. “This isn’t the environment versus economics. These coastal communities are vibrant and rely on park visitation for their livelihood. … This is propping up an industry that nobody wants at the expense of an industry that everyone loves.” Lund says that administration efforts to lease on-shore mineral rights near parks, roll back offshore safety rules, and weaken regulatory agencies has done little to assuage advocates’ fears.

The barrier islands of Channel Islands National Park generate a unique environment by mixing cold and warm currents off California’s coast, spiking the food supply and creating a diverse ecosystem some biologists say rivals the Galapagos Islands. The smaller islands are usually visited by kayakers and dayhikers; larger islands are big enough for overnight trips.

In 1969, an oil spill near the park saw volunteers in boats trying to mop up petroleum with straw, and prompted the country’s first regulations on offshore oil drilling. In 2015, just after another spill that shut down beaches on most of southern California’s coast, Kristen Hislop, marine conservation program director for the Environmental Defense Center, a law firm founded in the wake of the first spill, drove out to the water. Where oil was washing onshore, she recalls, people were struggling to collect it from the waves in buckets and to rescue fish and birds.

“California hasn’t been included in any new lease sales since 1984 and this plan opens up pretty much all U.S. waters,” she says. “That also includes areas where we’ve fought off new leases for some time now.”

California may not lead in industry demand because it can be expensive to drill there, and the industry faces staunch local opposition. Counties and cities are at work on resolutions to ban on-shore infrastructure for the industry, Hilsop says, and the center is supporting those efforts.

Big spills catch headlines when they happen, but despite the effort to mop them up, their effects can linger. Two decades after the Exxon Valdez oil tanker ran aground and unleashed 10 million gallons of oil into Prince William Sound in five hours, researchers could overturn rocks on Alaskan seashores and still find globs of the stuff, its chemical signature a match for what the tanker had been hauling.

Ocean health has ripple effects. It produces much as half of the planet’s oxygen. Its fisheries feed millions of people. Whether hiking the coastline includes spotting terns and shearwaters, glimpsing whales breaching or sea lions sunbathing depends on whether the nearby oceans provide habitat and food for them.

But marine conservation areas few and far between. Just 6 percent of the world’s oceans have any protections, a number well below the 30 percent recommended by research.

“Imagine hiking along a trail, along a sand bluff 100 feet high at Cape Cod where you can’t see any development in any direction, and hearing the surf pounding below. You feel like you’re on the edge of the continent—and in fact, you are,” says Murray.

That’s what these landscapes were set aside to protect: that moment of staring offshore at a big, wide open.

“Your imagination just runs wild with what’s in the distance, because you can’t see anything other than the horizon,” she adds. “It’s kind of hard to put a price tag on those experiences, but they can be impacted by visible offshore structures as well as any kind of offshore spill.”