Protecting the Future of Our National Parks

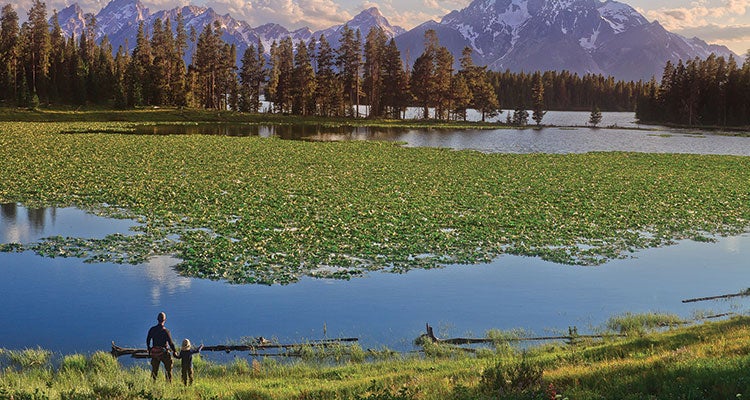

'Father and son view the Tetons from Heron Pond. (Photo by Kim Nelmark)'

Our national parks have a big, big problem. It’s you.

More specifically, it’s the mountains of string cheese wrappers, empty fuel canisters, greasy zip-top bags, leftover salami slices, disposable water bottles, and spent batteries that you, park visitor, leave in your wake. Yes, you pack out your litter and bury your poop and then congratulate yourself for leaving no trace. But the truth is, if you’ve ever tossed so much as a Clif Bar wrapper in a trailhead trash can, you’ve contributed to a problem that’s plaguing the national parks.

As environmentalists are quick to point out, you can’t just throw something “away,” because there is no such place. Every bit of the junk that gets tossed in the bin ends up somewhere. In the best-case scenario, “somewhere” is a recycling plant or composting facility. In the worst, it’s a landfill, where trash breaks down slowly, if at all, while emittingmethane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Today, nowhere on Earth is immune from our leavings, not even our most sacred places. To wit, though national park staff and concessionaires work hard to make sure you never see the trash accumulate, they’re moving 100-million-plus pounds of refuse out of the park and into the ground every year. And the parks have limited resources, thanks to chronic underfunding, so dealing with mountains of trash takes away from other services.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Last year, the National Park Service, Subaru, and the National Parks Conservation Association joined forces in an ambitious program to rid the parks of all waste bound for the landfill. (BACKPACKER joined the effort, too, partnering with Subaru to help support the campaign.) Because the only one who can make the plan succesful, saving America’s most beautiful places from this avalanche of our own making? That’s right, it’s you.

Enter Subaru, operators of the U.S.’s first zero-landfill car assembly plant: All of the Indiana factory’s waste is recycled or composted, with about 5 percent burned in a waste-to-energy power plant. After Subaru pitched the zero-landfill idea to help celebrate the NPS Centennial, they launched a pilot program in three iconic parks: Denali, Yosemite, and Grand Teton. After a year of research, the program is set to ramp up this year.

Make no mistake: Transitioning even one park to a zero-landfill model is a formidable challenge. Moving all 59 of them—which some stakeholders hope to do—is nothing short of monumental. But the NPS hopes that the lessons it’ll learn in these pilot parks (building partnerships with surrounding communities, improving infrastructure, and educating visitors) will provide a blueprint toward that goal.

To pull it off, parks will have to beef up recycling and compost collection, and switch to enviro-friendly plates and utensils in all cafeterias. Denali rangers are looking to partner with a local entrepreneur to turn cardboard into fuel for pellet stoves. Last summer, the Grand Teton Lodge Company started saving all kitchen scraps from the Jenny Lake Lodge and donating them to a local farmer for chicken feed. And this year at Yosemite, diners at concessionaire properties like Half Dome Village and Degnan’s Deli will see package disposal information, much like when restaurants post calorie counts. “We’ve created shelf labeling that says, ‘This is landfillable packaging,’ ‘This is recyclable,’ ‘This is compostable,’” says Aramark’s Leisure Division Director of Sustainability and Engineering Allison Gosselin.

But all these in-park measures—more signs, more dumpsters, more water-filling stations—can only go so far. A truly successful zero-landfill program is like Leave No Trace on steroids: Not only do you have to dispose of your trash properly, you also have to create less waste in the first place. “Trying to engage on the bottom rung, with recycling and composting, that’s too late,” says Lin King, zero-waste manager at the University of California-Berkeley. Before you even set foot in the parks, you’ll need to pack your reusable coffee mugs and water bottles, buy your gear (right down to batteries and bug spray), and plan your menus.

That brings us to the hard part: Getting visitors to change their behavior. So what works best when it comes to getting people to act? “What we’re finding routinely in our studies is that you have to tell people why,” says Ben Lawhon, education director at Leave No Trace and a consultant on the NPS zero-landfill initiative. “If I take all of my trash outside of the park, or I use the three disposal bins [compost , recycling, and landfill] appropriately, how does that help the Tetons?” Look for a highly visible campaign to educate the public about the cause and effect of trash disposal. And expect the NPS to look for ways to quantify for visitors that their actions do make a difference.

Picture this future: One day soon, Denali, Grand Teton, and Yosemite—and perhaps the rest of the national parks—could remove every last garbage bin. Rangers could focus on campfire talks and wildlife studies, rather than dealing with tons of garbage. The air would actually be cleaner, with fewer trash trucks on the roads. Of course, getting there won’t be easy, and nobody expects such a triumph of teamwork, education, and environmental consciousness to happen overnight. But, as a society, we’ve won coups like this before—witness municipal recycling programs, which didn’t exist a generation ago.

Ultimately, the answer to the problem is the same as its source: It’s you.

#DontFeedTheLandfills

Be a Zero Hero: Backpackers can help the national parks eliminate trash by packing wisely.

Pay Attention to Packaging

Skip store-bought, pre-packaged, single-serving foods and hit the supermarket’s bulk bins (when possible) to create your own meals, coffee, and snacks sans extraneous packaging. When prepping foods for the trail, use durable containers or look for vittles with recyclable or compostable wrappers.

5 More Threats to the National Parks

1. Too Many People

Park visitation hit an all-time high in 2015, with more than 307 million total visits (14 million more than 2014) and 57 of 59 parks reporting record-breaking attendance. And while that’s great news for conservation, it also means traffic on thoroughfares, clogged trails, hard-to-land campsites, and stressed wildlife.

Solutions Implement more public transit to and in the parks, encourage people to visit during off-seasons and -hours, and direct them away from overflowing tourist zones. “We want people to enjoy the outdoors,” says Yosemite National Park Superintendent Don Neubacher. “We just need them to spread out.”

2. Wildfire

In 2013, the third-largest wildfire in California history torched 77,000 acres at Yosemite, filling the valley with smoke and threatening the park’s sequoia groves. In 2015, blazes obscured vistas and shut down campgrounds and trails at Glacier, North Cascades, and Crater Lake, including a chunk of the Pacific Crest Trail. And this past spring, one of the largest wildfires in Shenandoah’s history closed part of the Appalachian Trail for more than two weeks. Experts predict more frequent and more intense blazes (so-called megafires) as increasingly hot, dry weather patterns meet forests choked with dead fuel left over from decades of fire suppression.

Solutions Parks may need to set more prescribed burns to clear out dry fuel, which can help keep wildfires from getting out of control, says Christina Boehle, NPS Division of Fire and Aviation Management Fire Communication and Education Specialist.

3. Warmer Winters

Elevated temperatures mean less snowfall in the winter, which means a less reliable snowmelt in the spring. That means drier summers, which lead to changing plant communities (such as a steadily rising treeline), which puts pressure on wildlife.

Solutions “We can’t generate bigger snowpacks,” says Dan Fagre, research ecologist for the USGS’s Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center. But in some parks, scientists are trying to help species survive the changing climate, like relocating bull trout within Glacier.

4. Too Little Money

Budget shortfalls have forced almost every park unit to delay critical maintenance work on roads, campgrounds, and buildings. In 2015, the construction backlog reached $11.9 billion—five times 2015’s operating budget. Parks may close access to facilities in poor repair if it becomes a visitor safety issue. As visitation and new costs pile up—like newly designated national monuments and climate change adaptation projects—parks will continue to feel the pinch into the next century.

Solutions “I think that, in the future, funding is going to be somewhat different,” says NPS Director Jonathan Jarvis. “The bulk of the funding will still be federally appropriated, but will have to be supported with philanthropy from private foundations and corporations.” Translation: Cash donations from nonprofits will become even more important.

5. Rising Seas

Climate change means that much of the NPS’s more than 12,000 miles of shoreline, from the bluffs of Acadia to the Everglades’ wetlands to the rugged Pacific coast of Point Reyes and Olympic, are in danger from intensifying storms or, worse, complete inundation by rising seas. Globally, experts predict the oceans will rise 1 to 4 feet or even more in the next 100 years, threatening the parks’ pristine beaches, historic buildings, and archaeological resources.

Solutions The bad news: It’s probably too late to halt the encroaching seas. Instead, the parks are planning workarounds. Rangers have dumped extra sediment on the barrier islands at Gulf Islands National Seashore, crews are shoring up the fort at Dry Tortugas, and officials are fast-tracking surveys of archaeological resources at parks like Olympic and Alaska’s Bering Land Bridge National Preserve.