Here’s How the Presidential Candidates’ Public Lands Plans Stack Up

'Shelly Prevost; Phil Roeder'

In the 11 years that Phil Francis was Great Smoky Mountains National Park’s deputy superintendent, he saw air quality in the park improve by 80 percent. That both lifted a curtain of smog from the forested ridgelines and reduced the number of respiratory illnesses among people living in the surrounding area. The Clean Air Act had cleared the air.

“Whoever is elected president has to be committed to making sure the places where we live on this planet is improving and well taken care of,” says Francis, who worked for the National Park Service for 41 years and now chairs the executive council for the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks, an organization representing more than 1,800 former Park Service employees and volunteers. “Both candidates who have a chance of winning the Democratic nomination for president seem to be committed to making improvements to our environment. I think both are interested in addressing global climate change, which is important.”

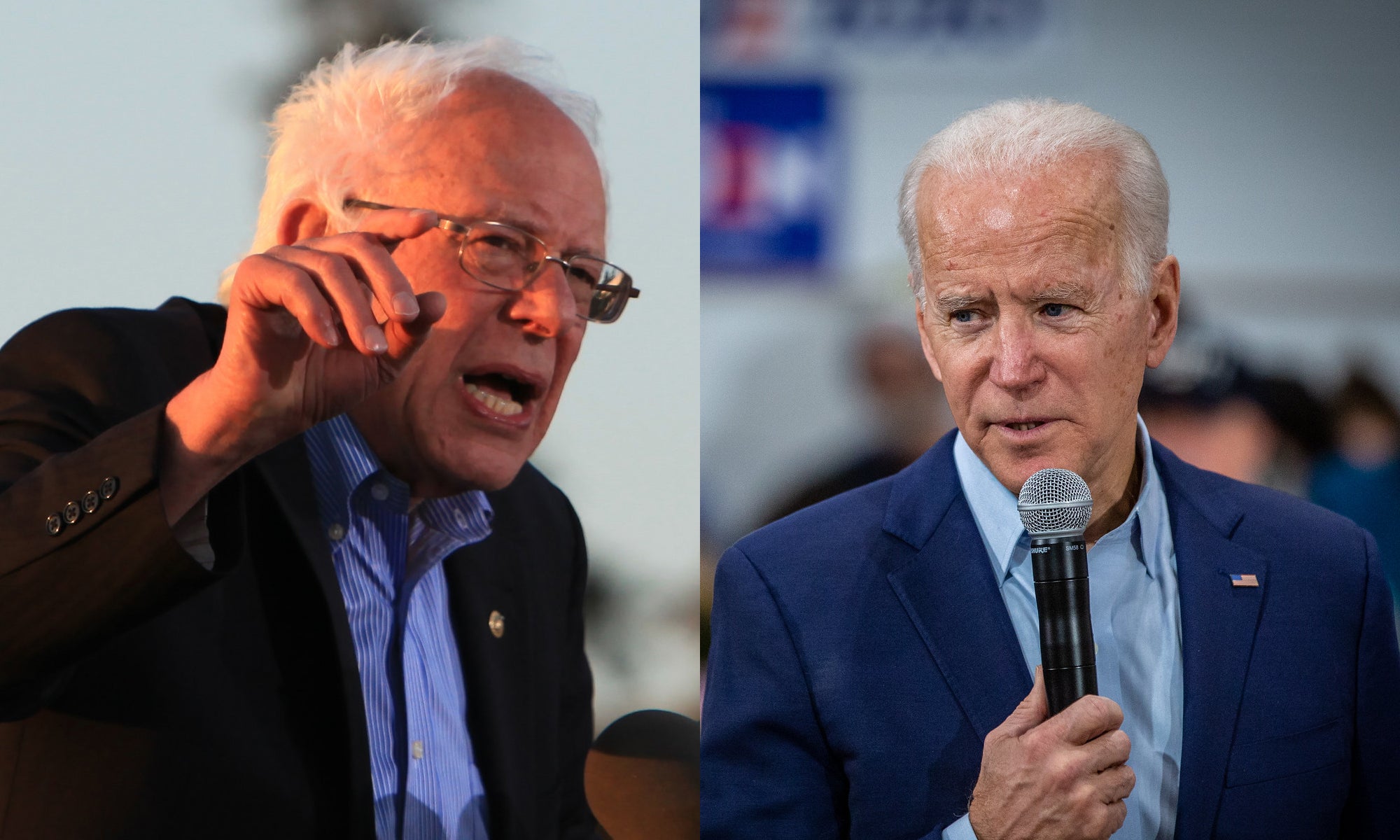

From their budget to their regulations and enforcement, presidents holds sway over public lands. A gulf in ideology separates the leading Democratic presidential candidates: former Vice President Joe Biden, a moderate with years of experience wrangling the establishment, and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist arguing for upending broken systems. When it comes to their public lands platforms, however, there’s little difference. Both draw their positions in broad strokes that have left conservationists hungry for more details.

“There is plenty of room for both Sanders and Biden to flesh out their vision for parks and public lands,” says Kate Kelly, public lands director with the Center for American Progress. “The bulk of their policy proposals are embedded within their climate plans—and that’s a great place for them to be—but it is, at this stage, limited to a couple bullet points. I think as voters are considering how to make a decision, they are owed a much more detailed and thorough plan on public lands.”

A strong public lands plan could help the candidates at the ballot box: A State of the Rockies poll of 400 voters throughout the intermountain West found that the environment was a primary factor for 44 percent of voters.

“The numbers are way up from the last time we asked the question,” says Dave Metz, who worked with Colorado College on the poll.

Those results indicate recent policies have animated voters around this issue, he says. Only a quarter of those polled supported maximizing the public lands available for domestic energy production, as the Trump administration has directed land managers to do.

Both candidates’ climate platforms set ambitious goals for curtailing emissions by 2050, with some variance in speed and scope, and thread in points on public lands. They aim to reduce fossil fuel development on public lands, which are currently the source of a quarter of the nation’s emissions, and both pledge to reverse the downsizing of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments and protect biodiversity by increasing the amount of protected land in America from 14 to 30 percent by 2030. Sanders also calls for a “Green New Deal” that would aim to combat climate change while creating new jobs, including a “reimagined” Civilian Conservation Corps to build and maintain trails, plant trees and other native species, and clean up plastic pollution.

Slowing climate change itself could help preserve national parks. Warming trends are threatening to end glaciers in Glacier National Park and Joshua trees in Joshua Tree National Park, and convert Yellowstone from conifer forests to grasslands.

But some public lands advocates say their plans are still too vague for comfort.

“I hope they understand they really need to develop some understanding about how important public lands are to those of us who live out here in the West,” says Mark Squillace, associate dean for faculty affairs and research at the University of Colorado Law School.

Among other points conservationists would like to see the candidates address are fully-funding land management agencies that have seen budget cuts over recent decades, re-thinking multiple use on public lands, and re-engaging with indigenous communities on management decisions. Senator Elizabeth Warren, former South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg all put out more detailed public lands plans which incorporated some or all of these details.

“One tweak we’ve been encouraging candidates to think about is that it’s a climate crisis, but also it’s a nature crisis. We’re losing natural areas at an astounding rate,” says Dan Hartinger, director of government relations for the Wilderness Society Action Fund. “We can’t just be focused on tailpipes and smokestacks. … We need to be reinvesting in and protecting our natural systems.”

Whichever candidate secures the nomination, it’s a virtual certainty that their public lands platform will differ significantly from President Trump’s record. The last three years have seen an unprecedented series of rollbacks on protections for public lands, fast-tracked oil and coal development, and weakened bedrock environmental laws including the Clean Air, Clean Water, and National Environmental Policy Acts. The president’s budget has also cut funding for the Department of the Interior and other federal land management agencies each year. (Both Democrats have pledged to reverse those policies.)

There have been some gains, too: Trump recently tweeted support for funding the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which supports public lands and close-to-home green spaces, and he has pushed to improve access to public land inholdings, which are surrounded by private land. The Restore Our Parks Act, which would help pay for deferred maintenance at national parks with money from energy development on public lands, is currently working its way through the senate.

But for Kelly, and many other advocates, those small steps just aren’t enough.

“It is, I think, an easy decision as to which of the candidates have future generations in mind when they look at public lands,” Kelly says.