Bad News Triple Header from Yosemite and Great Basin

Image via Flickr

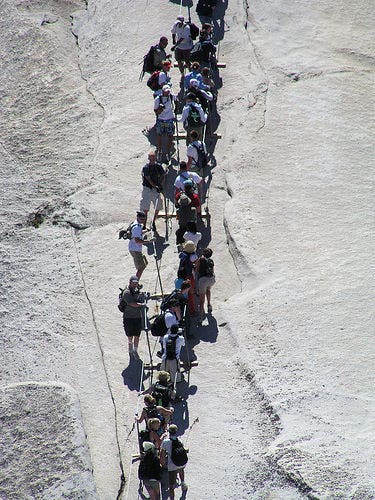

Lessons from Half Dome

On Saturday, June 13th, hiker Manoj Kumar, 40, fell to his death off the Half Dome cables in Yosemite Valley. His fall occurred one week after another hiker fell 300 feet but survived. Rangers had to evacuate 41 gripped hikers from the route. You can read more on this earlier Daily Dirt post, and in this Backpacker forum. Both include first-hand eye-witness accounts. Here’s my take:

[] Many people underestimate exposed scramble climbs. While weather, heavy traffic, and often-unqualified hikers make the phenomenon worse on Half Dome, the same sort of accident occurs routinely on less famous or traveled scramble peaks. Climbing any Class III or IV route requires thousands of individual moves. It only takes one miss. You can’t expect a perfect record, but that’s what soloing requires – even when you’ve got a hand line. It’s strictly for very high-mileage, well-trained climbers, and they die by the dozens too. Half Dome averages about three deaths a year, but relative to the visitor numbers, that’s not a particularly high figure.

[] The safety answer on Half Dome is a pair of tough leather gloves (to prevent frayed cable wires from tearing your hands), along with a harness and carabiners rigged via ferrata style to attach you to the line. A missing step or two on the ladder (as was the case here) isn’t really the cause, because people fall off perfectly good ladders and trails all the time. If you’ve got a safety cable or handrail, it’s crazy not to use that for anchoring too, or at least have the ability to do so – just like you should always carry a light rope on steep peaks. On a slab like Half Dome, where you’d never actually hang in space, all you’d really need is a rope waist loop with two 3-foot extensions leading to twin carabiners. The Park Service should probably require some sort of leash, and put a sign to that effect at the base of the cables. Most visitors won’t violate posted regulations if numerous other groups are enthusiastically pointing out their transgression.

[] One of your biggest dangers on popular mountains isn’t the peak, it’s everyone else. Iconic mountain summits attract huge numbers. On busy peaks like Half Dome, the Grand Teton, or even Everest, slow-moving crowds are ALWAYS a problem. Many people on climbs like these will continue ascending even when alarmed or in over their heads, simply because everyone else is. When conditions deteriorate, as the weather did during this incident, crowds are guaranteed to freeze up, trapping you in the train. This often happens on descent because of afternoon storms, fatigue, and the fact that descents look and feel scarier than ascending. Avoid crowd bottlenecks by starting out early and staying ahead of everyone else. That is your only solution. Manoj Kumar’s death is tragic, but it could have been worse. While falling, he might have tumbled into others and sent them falling too….like the Mt. Hood accident/heli crash several years ago where multiple rope teams were flossed off the summit couloir by a falling party – on a bluebird Memorial Day weekend.

[] On the bright side: Congrats to reader/witnesses Eric and Aydee on their impending nuptials! He proposed on the summit. She accepted. Kumar took a photo of them together.

Body Of Missing Yosemite Concession Employee Found

On Sunday, June 14th, Christopher Hale, 23, of Gainesville, Florida, an employee in training for DNC Park and Resorts, Yosemite’s main concessionaire, was reported missing. On Monday, searchers found his body beneath a cliff near Mirror Lake in eastern Yosemite Valley. He had apparently fallen to his death.

[] I’ve said it a zillion times, but it still bears repeating: Unroped scrambling is the biggest single cause of backcountry fatalities. Don’t do it, especially when you’re alone. Climbing down steep moves is always more difficult than going up, which makes retreat difficult once you ‘sketch out’.

Missing Hiker Lost Overnight Descending Wheeler Peak in Great Basin NP

From the National Park Service Morning Report, June 17th: “Late on the evening of June 8th, the county sheriff’s office notified the park’s chief ranger that they’d received a 911 call reporting an overdue hiker on the Wheeler Peak Trail. The responding ranger determined that a 56-year-old man had become separated from his hiking party while descending from13,063-foot Wheeler Peak, Nevada’s second-highest summit. Weather conditions had been poor during the descent, with low clouds, snow flurries, wind gusts up to 30 mph and visibility of approximately 200 feet. The man had not been seen since approximately 5 p.m.

“Family members and other campers had been unable to locate him, finding only tracks in a snow bank suggesting he had left the designated trail. The missing hiker was reported to be in good physical condition with no known medical problems, but was not carrying food, water, flashlights, maps or any other equipment. He had left his daypack along a lower part of the trail on the ascent to reduce the weight he was carrying.”

Apparently the unnamed victim descended down the mountain’s northern flank, then veered west (rather than curving eastward toward trailhead). When clouds broke he realized his error, but was too tired to climb back up. He made for distant ranch lights and spent the night in an unoccupied dwelling, then hiked back into the park the next day, where he encountered a fish survey crew who reunited him with his family.

[] People dump weight too readily. I’m all for ultralight travel, but 5 or 10 pounds isn’t going to make or break your ascent, while zero pounds can definitely ruin your day. Setting down a pack, you can easily get stranded away from your gear. I once spent an hour grid-searching for my backpack (and water) after doing that in Death Valley’s Funeral Mountains.

[] This separation scenario happens to peak baggers all the time. DO NOT separate on summit descents, or lose visual contact in bad weather. Climbing and descending a peak is like moving in and out along the spokes of a wheel, or going up and down a series of forking tributaries on a stream. When climbing up toward the peak (or downstream on a river), all routes eventually converge, so getting lost is tougher. When descending a peak (or heading upstream on a river system) all routes diverge, and it’s much easier to get lost. But groups often split up on descent, because ‘it’s just a cruise’ back down.

O.K., That’s all for now. There were a couple more instructive incidents that came up, but two of my friends just got spanked out of the Wind Rivers by rain, snow, and lightning, so they’re coming down to Torrey as a fallback plan. We’ll be, uh, gear testing until Monday. I’ll try to heed my own advice and stay out of the news – never a sure thing. –Steve Howe