4 Sneaky Signs It’s Time to Replace Your Hiking Shoes

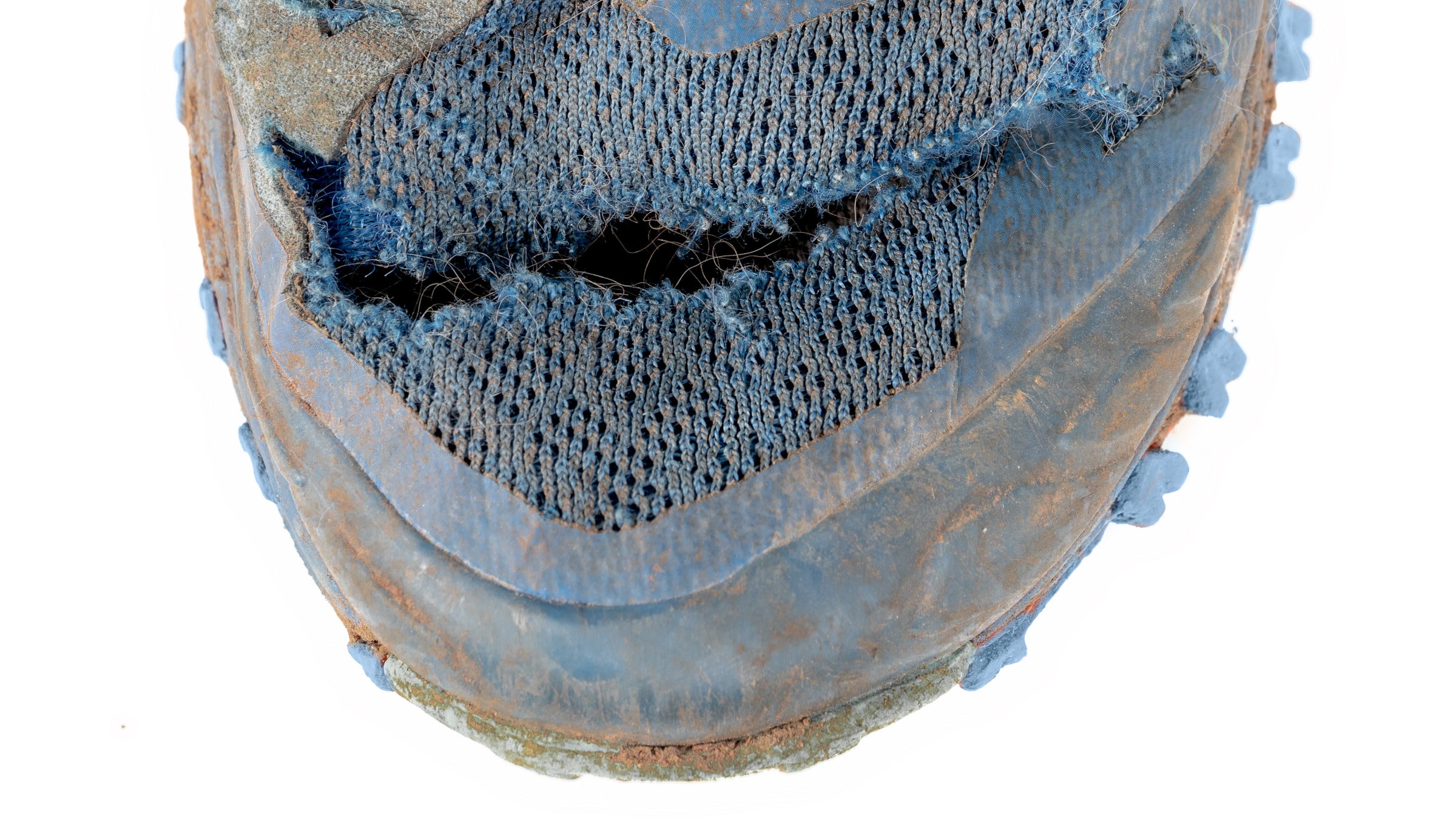

Ripped hiking shoe (Photo: Petra Richli / iStock via Getty)

Like most backpacking apparel, your hiking shoes have a definite lifespan. But unlike a patched-up jacket or crusty socks, a degraded pair of hiking shoes can impact everything from toe protection to hip alignment, meaning it’s more important to replace these than it is to swap out your grungy down jacket.

Common wisdom allows hiking shoes a lifespan of 500 miles, but this depends on the shoe style, brand, and individual model.

For example, a lightweight, flexible trail runner like the Saucony Peregrine lasts me around 350 miles. Trail running shoes typically are typically built with a mesh-heavy upper, a light and responsive midsole and a flexible rubber outsole often built with patches of exposed foam. The upside is less weight on your feet, but most people will replace them sooner thanks to blown-out uppers and midsoles that compress a lot faster than a stiffer hiking shoe.

A true hiking shoe like the Merrell Moab 3 is made with thicker materials, additional overlays through the upper, and reinforcement through the full-rubber outsole and toe cap. These shoes are heavier and less breathable than a trail runner, but most hikers can get 500 miles out of most pairs before material failure and midsole compression.

Hiking boots like the Salomon X Ultra Mid are typically the most durable, with additional overlay reinforcements, little (if any) mesh, and burly outsoles with mid-height wraps and heavier materials. I can get 500 miles or more out of these shoes, with noticeably less material degrading than lower-cut hiking shoes.

Obviously there are outliers in each category, from the Altra’s popular but notoriously short-lived Lone Peaks (I’ve had a pair completely fall apart within 150 miles) to heavy boots like the La Sportiva Nucleo that will last through the next ice age.

What You Can See: Peeling Rubber, Blown-Out Uppers, and Smooth Outsoles

Most backpackers are familiar with the outward signs of a tired hiking shoe—peeling toe caps, blown-out sidewalls, and a smoothed-over outsole with greatly reduced traction, to name a few symptoms. Peeling toe caps are mostly cosmetic, but are often the first sign that the glue is failing, and you can expect some separation along the outsole as well. This usually means little more than a more aggressively stubbed toe, but I’ve had a stick stab through the exposed mesh at my toe after the toe cap peeled off, and that wasn’t fun.

Upper blowouts are more common if your gait pattern tends towards pronation or supination. Pronators roll their feet inward, and might see bulging mesh or eventual wear-throughs along the widest part of the forefoot, especially on shoes without much upper reinforcement. Conversely, hikers who supinate will often notice the outside edge of their shoe failing. A wider shoe or a wide toe box can help mitigate this, as can shoes with less mesh in the instep or outside of the foot.

Outsole wear can be the biggest frustration when it comes to worn-out shoes. Regardless of lug pattern or rubber compound, all outsoles will wear down eventually, and faster if you hike on rocky or uneven surfaces. Most trail-specific outsoles have lugs between 3.5 and 5.5 millimeters, with sharp, multidirectional edges for traction going up and downhill. (Remember that the softer rubber on trail runners wears down faster, and can feel disastrously slippery on loose surfaces and rocks). It helps to look for an outsole with a high-quality rubber compound (I trust Vibram more than most brands). If you’re concerned about traction or rugged surfaces on an upcoming trip, choose a shoe with a full-rubber outsole and deeper lugs.

What You Can’t See: Midsole Collapse

While those outer elements are fairly easy to spot, midsole collapse is arguably the most important part of a dead hiking shoe, and much harder to spot. My advice If the rubber on your shoe is flapping and the upper is hole-ridden, it’s safe to assume it’s losing midsole support too.

A shoe’s support largely degrades from the inside, impacting everything from lateral stability to stride support to ground protection. Most modern hiking shoes, boots, and trail runners use a high-tech EVA compound for the midsole, with some brands building in proprietary nitrogen-infused dual-density foam with foot-mapped compounds.

Regardless of the precise material, a hiking shoe midsole does more than just cushion your feet from the ground over the course of 12-hour days. The midsole is also critical for stability and support. The more stable your stride and underfoot platform, the better your balance and the more torsional control you’ll have through your ankles, knees, and hips.

If you’ve ever kept plodding along in shoes past the end of their lifespan, you might have noticed extra knee pain during long days, odd ankle twists, and a general misalignment in your stride. This is more than likely due to an overly compressed midsole, which eventually provides little to no protection.

Similar to blown-out uppers, hikers who pronate or supinate will see exaggerated and uneven midsole compression as well. Eventually this off-balance wear-and-tear can impact everything from your feet to your ankles to your knees and hips. In this case, gait-specific after-market insoles can provide support and additional durability.

The Bottom Line: Don’t Let Your Shoes Overstay Their Welcome

Overall, you can expect between 350–500 miles from your hiking shoes, depending on gait, pack weight, shoe style, and terrain. Remember to look beyond the cosmetic failures and outsole, and consider whether the midsole foam has compressed past the point of return. If your uppers look solid but you’re feeling the ground beneath your feet and your knees are aching in new and exciting ways, your hiking shoes have probably lost their underfoot structural integrity and it’s time to turn them into your new favorite pair of dog-walkers.